Puzzle Laboratory Presents

A Guide to Twisting Puzzles

written by Michael Keller

October 2024

Table of Contents

Introduction

A Microhistory of Twisting Puzzles

A Quick Account of my Cubing History

A Brief Glossary of Terms Used in Twisting Puzzles

Solving the 3x3x3 Cube -- an Intermediate Solution

Picture Cube

Other Coloring Patterns

Shape Modifications

Fisher Cube

Mirror Cube

Twist 3x3x3

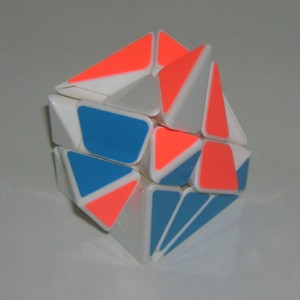

Super Skewb

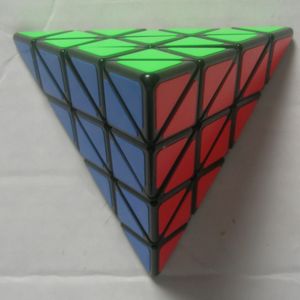

Master Pyramorphix

Fluctuation Angle Cube (Axis Cube)

Mixup 3x3x3

Magic Domino

Cuboid Puzzles (Larger Dominos)

Floppy Cube

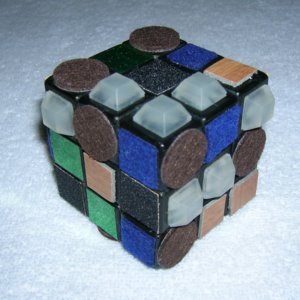

A Tactile Cube

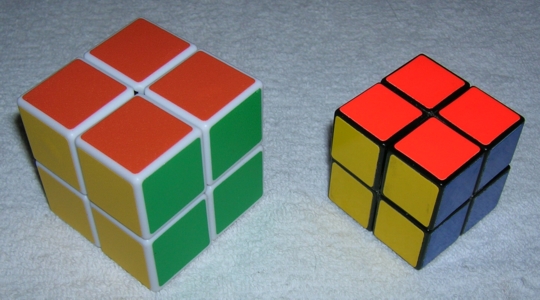

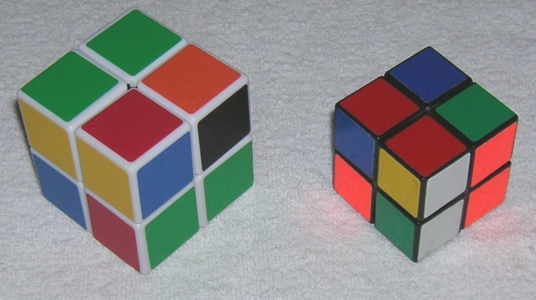

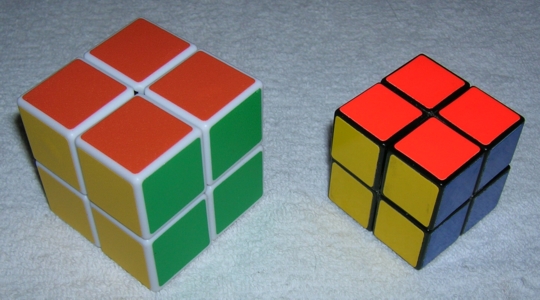

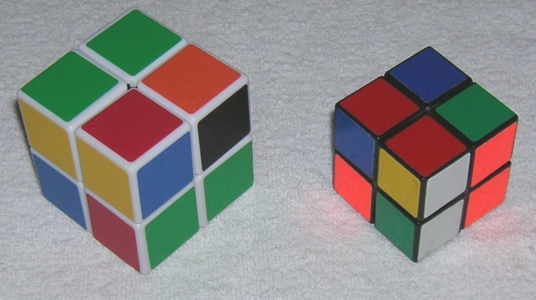

The Pocket Cube (2x2x2)

Rubik's Insanity -- a Scrambling Question

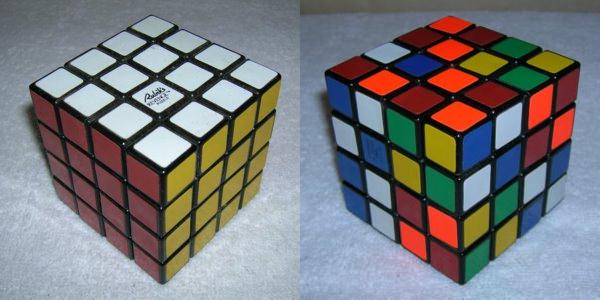

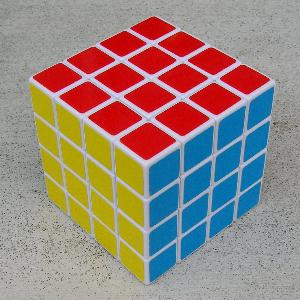

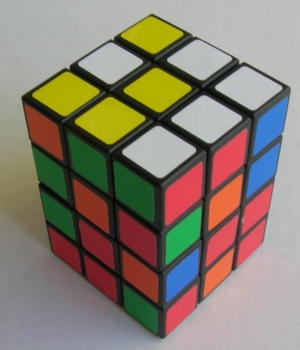

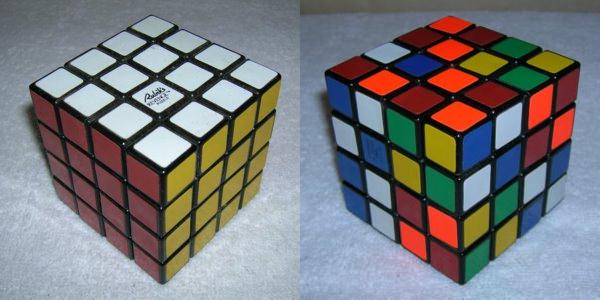

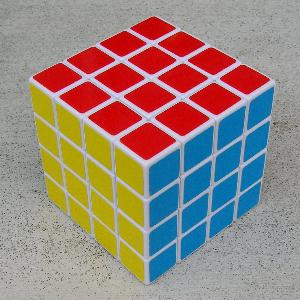

Rubik's Revenge (4x4x4 Cube)

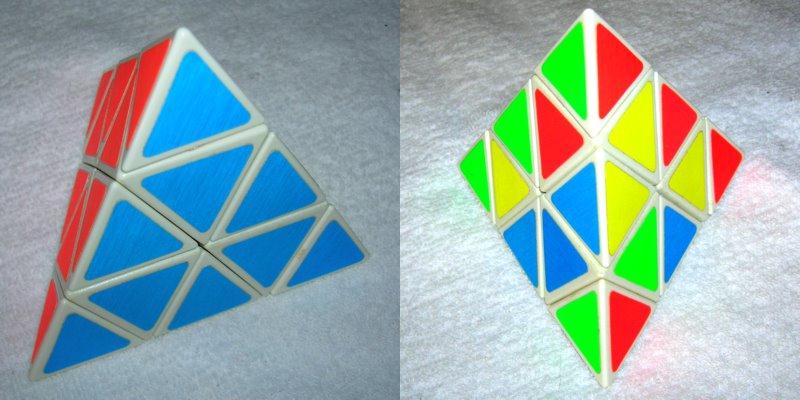

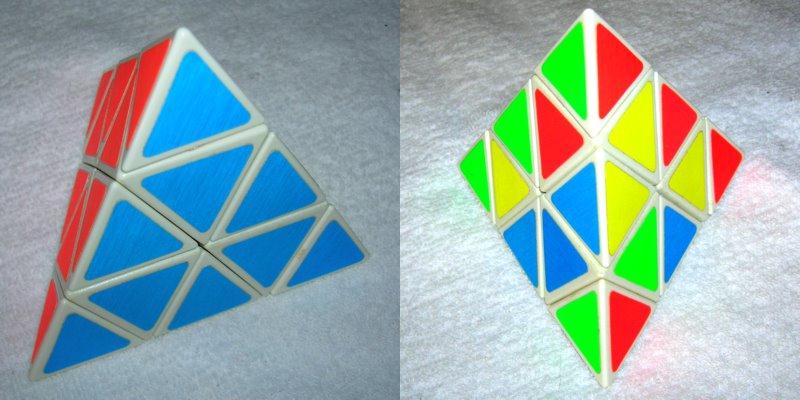

Pyraminx in 27 Moves

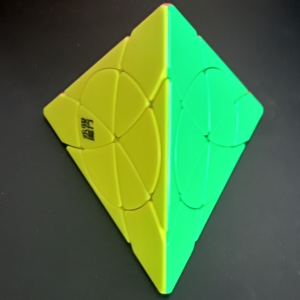

Petal Pyraminx

The Skewb

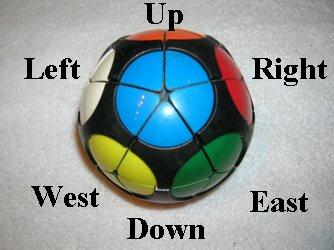

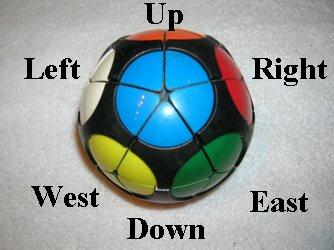

The Orb

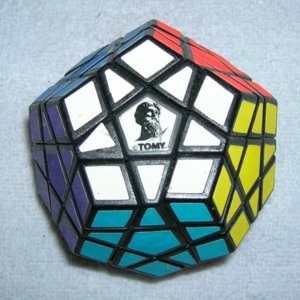

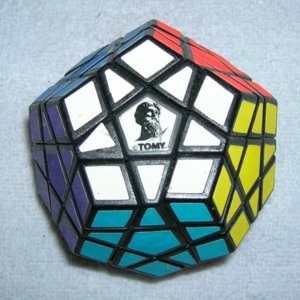

ImpossiBall and Kilominx

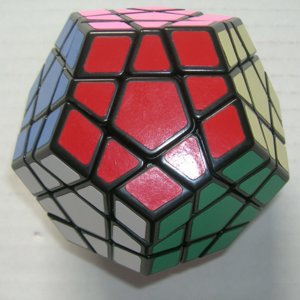

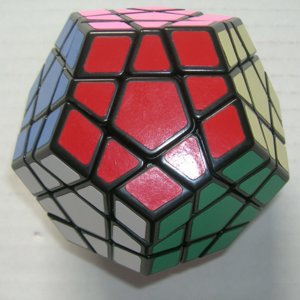

Megaminx

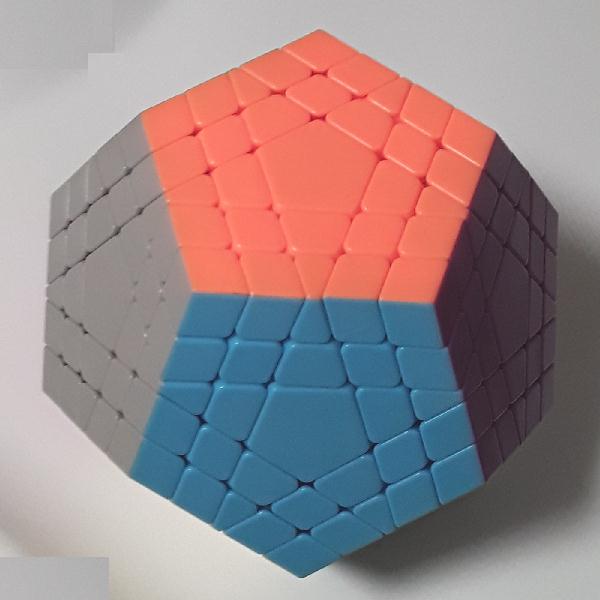

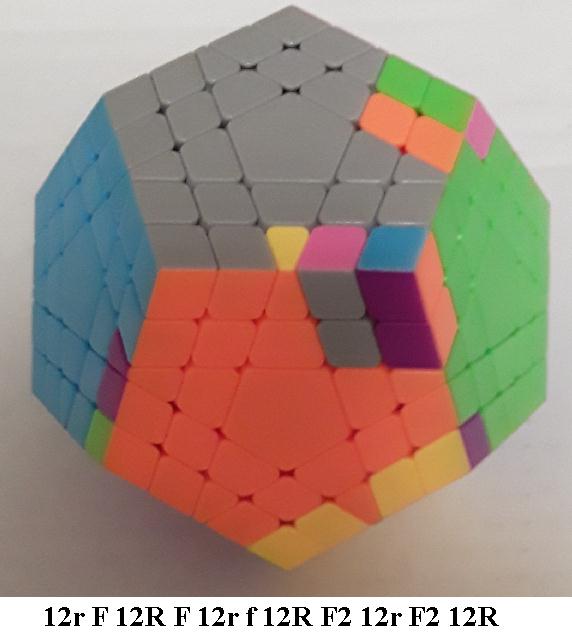

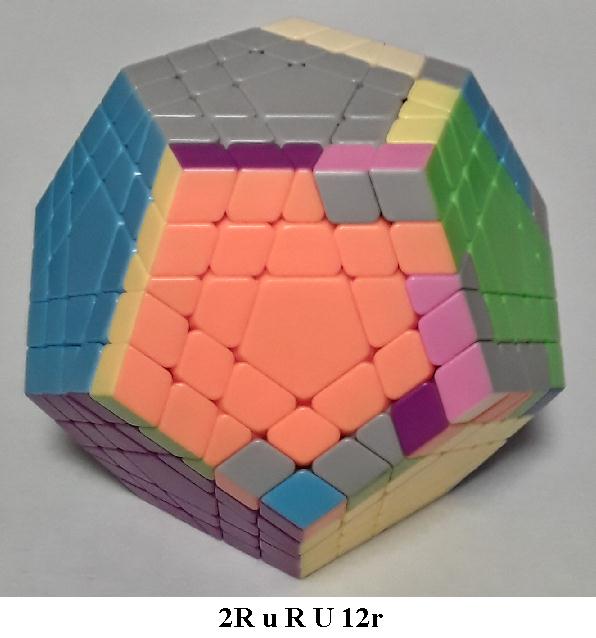

Gigaminx

Easiest Twisting Puzzles for Beginners

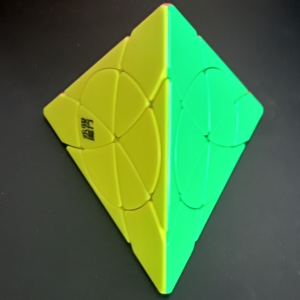

Disk Pyraminx

Ivy Cube

Dino Cube

Redi Cube

More Solutions Coming

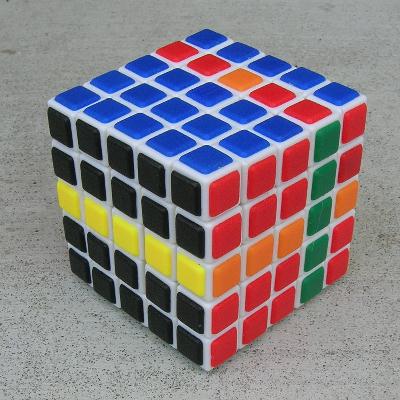

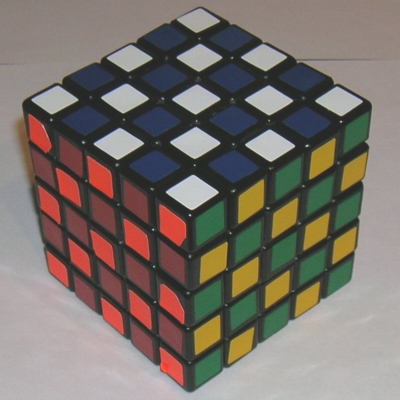

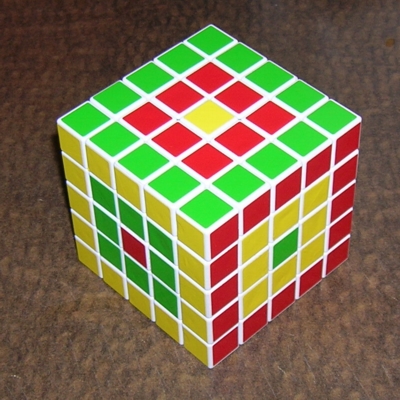

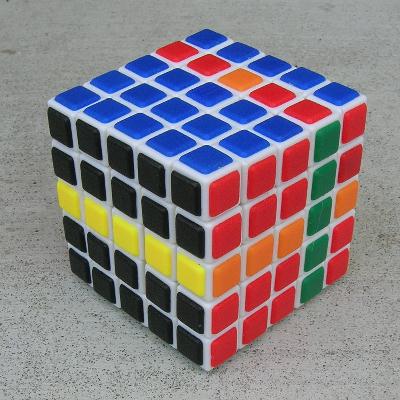

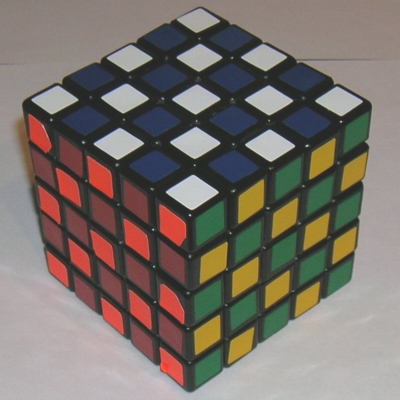

The Professor's Cube (5x5x5)

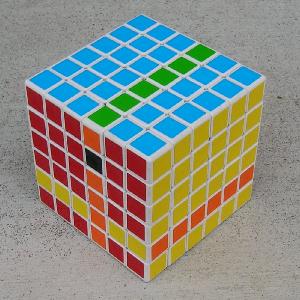

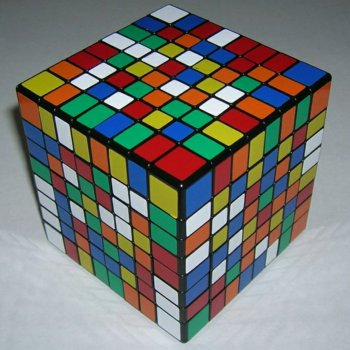

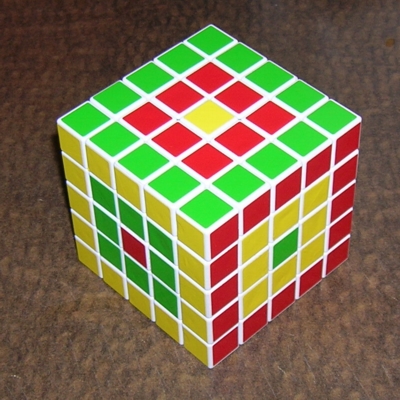

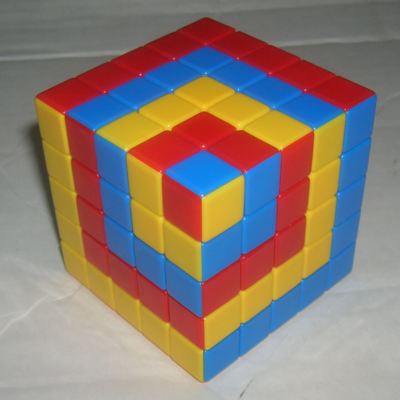

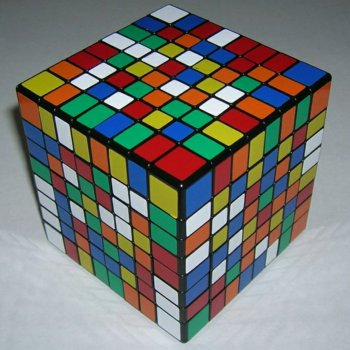

Larger cubes

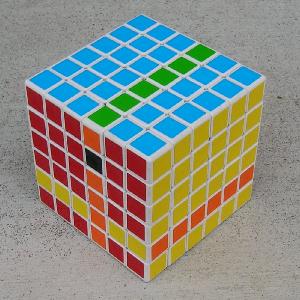

The 6x6x6 Cube

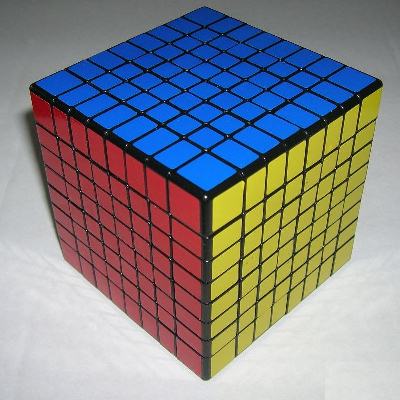

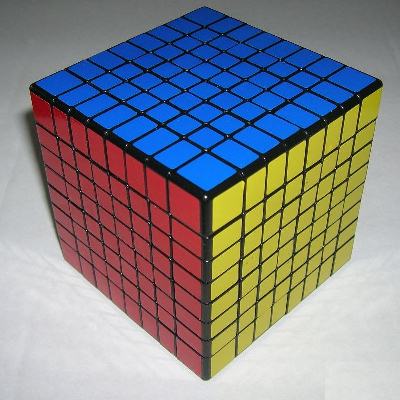

The 7x7x7 Cube

The 8x8x8 and 9x9x9 Cubes

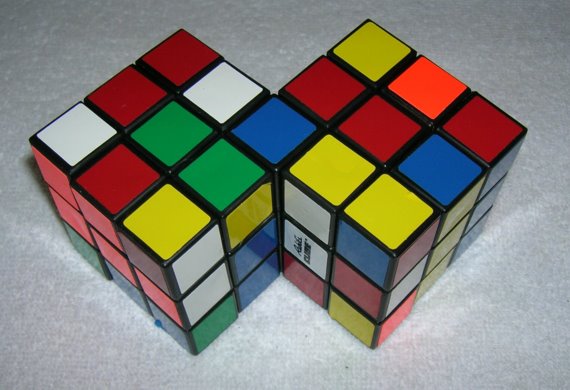

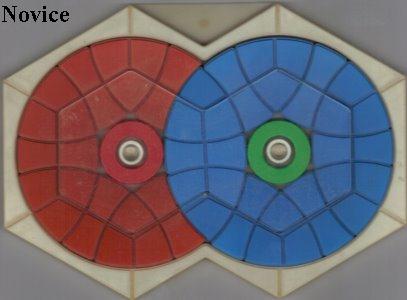

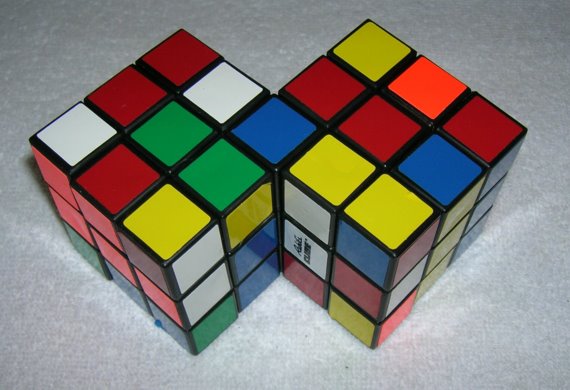

Siamese Cube

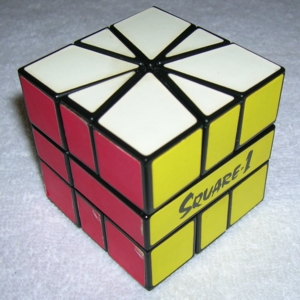

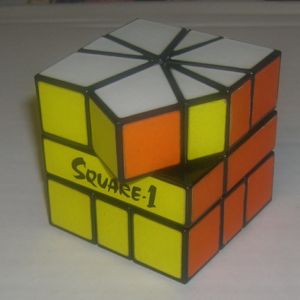

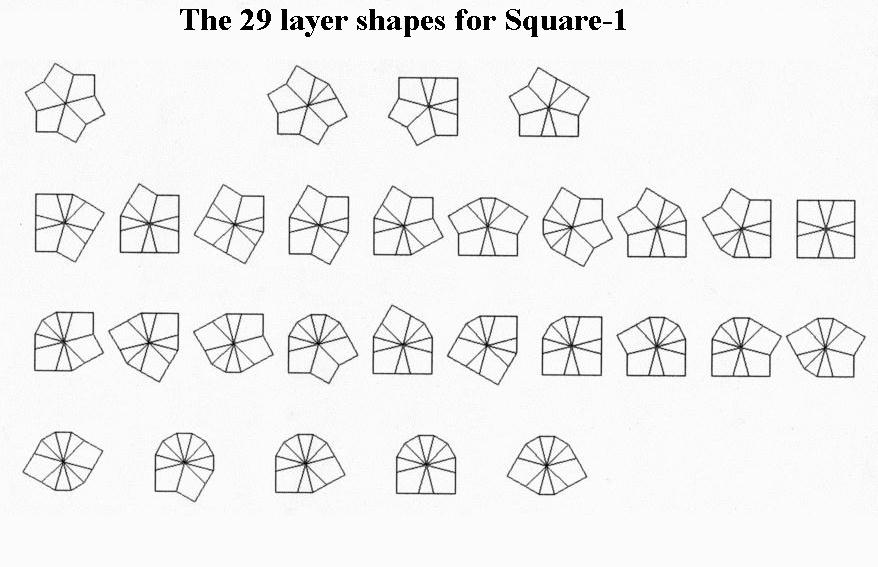

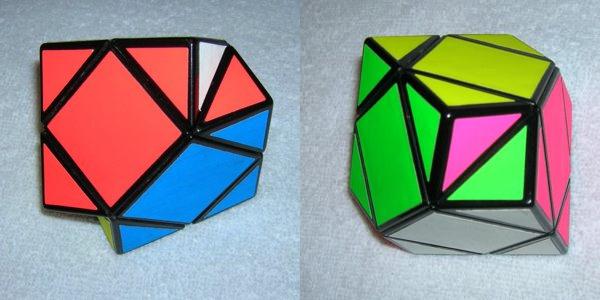

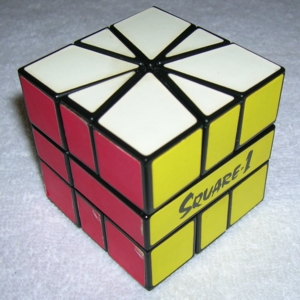

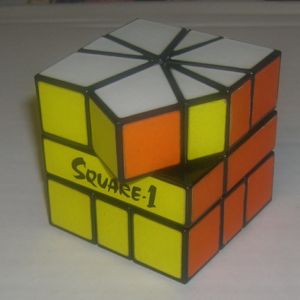

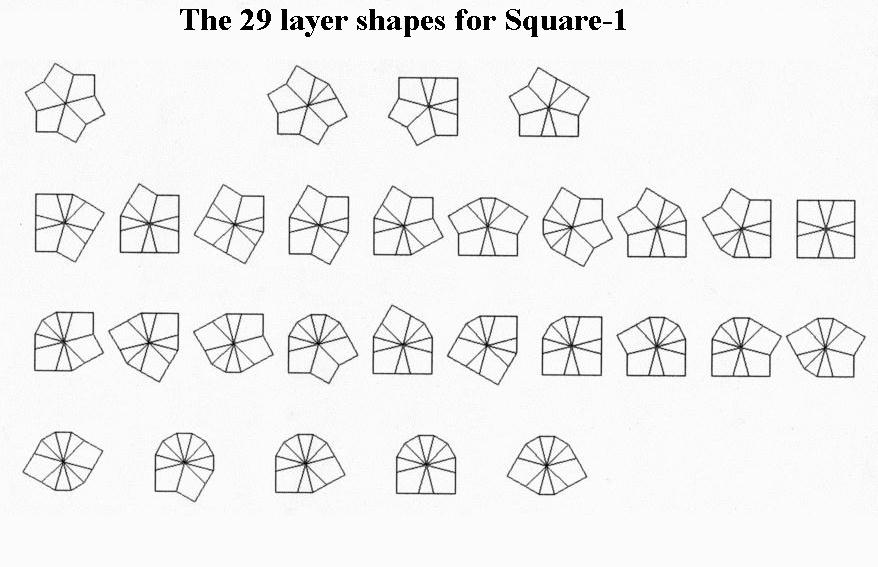

Square-1

Square-2

Alexander's Star

The Missing Link

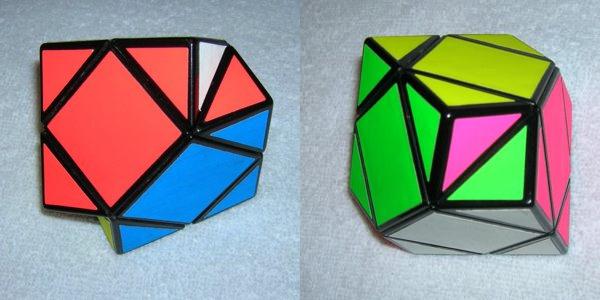

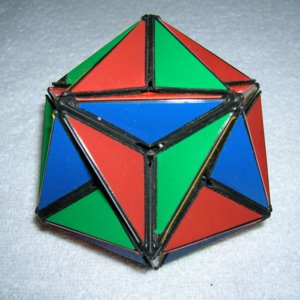

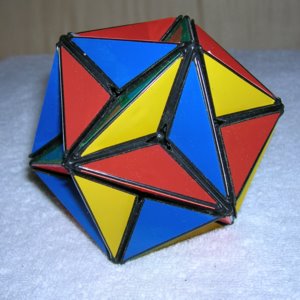

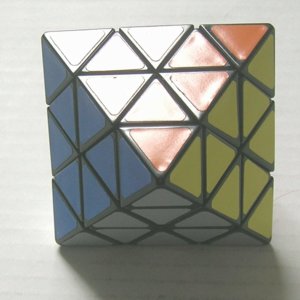

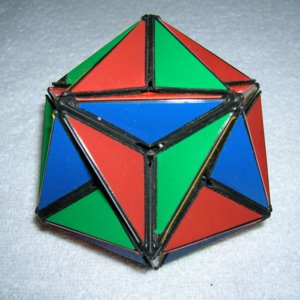

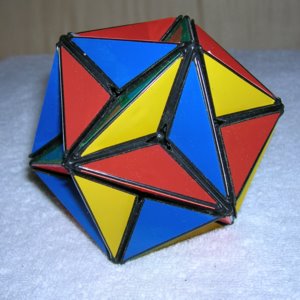

Vertex-Turning Octahedron

Puzzle Roundup

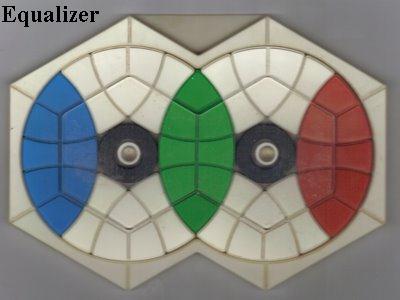

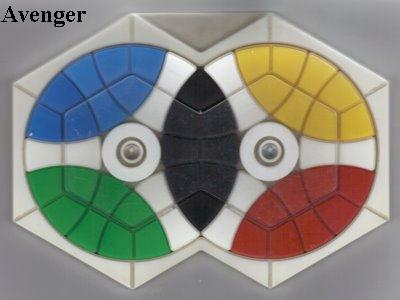

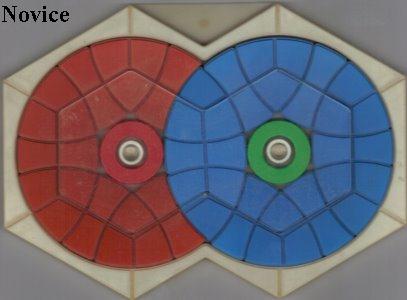

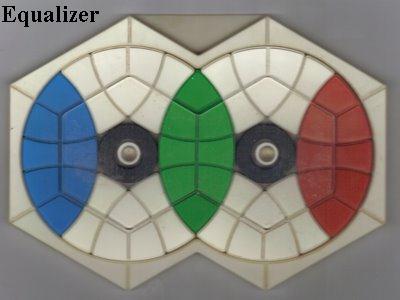

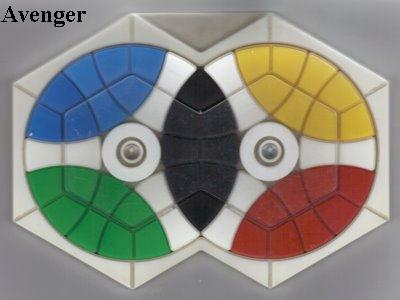

Engel's Puzzles

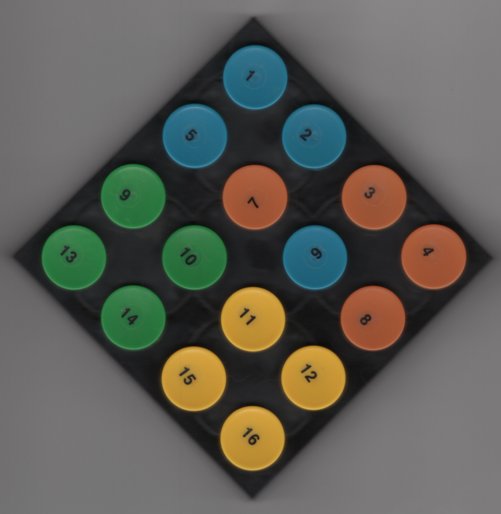

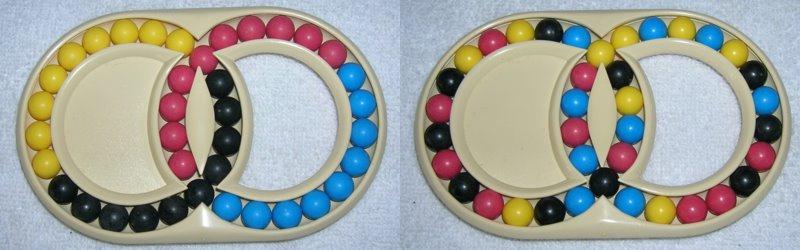

Top-Spin and Back-Spin

Smart Alex and Galaxy Lock

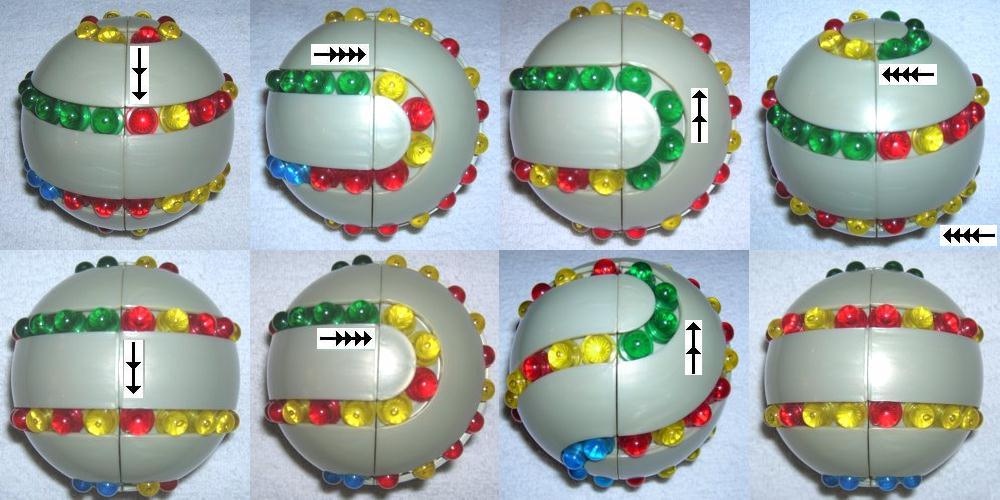

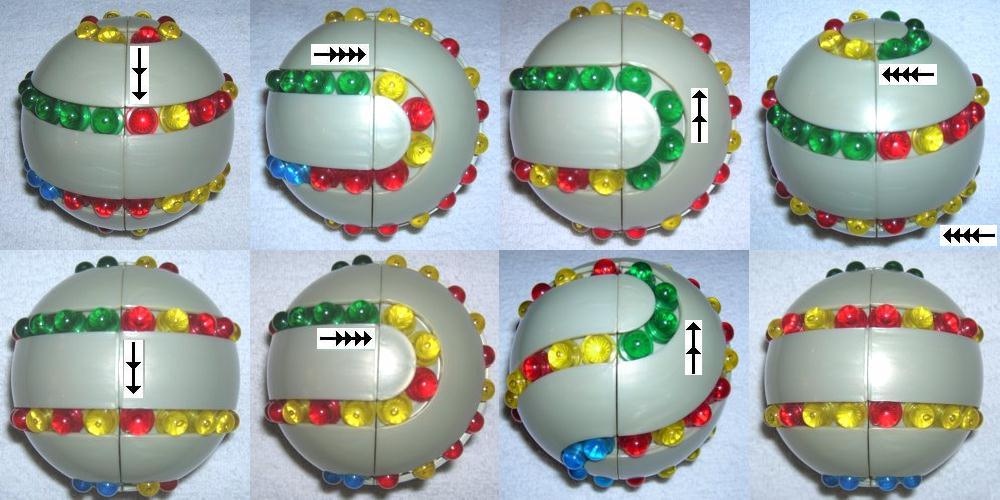

Masterball

Rubik's Clock

Gripple and Orion

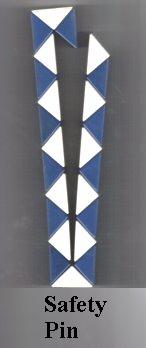

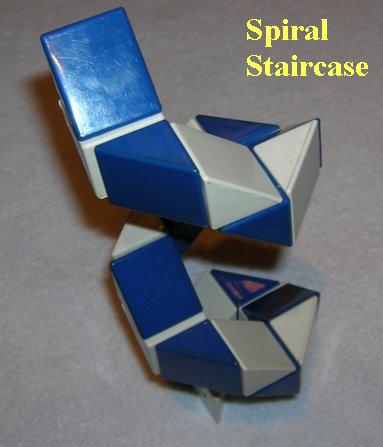

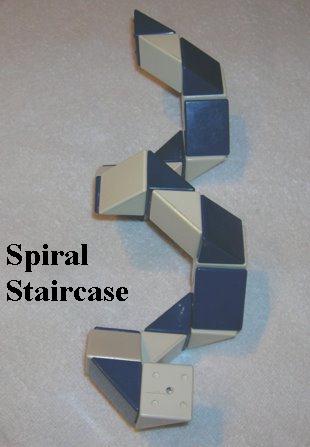

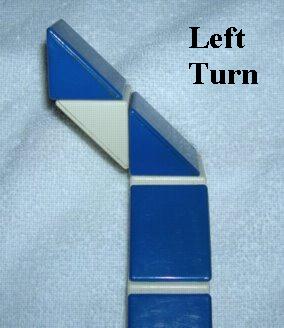

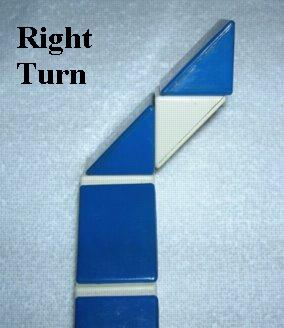

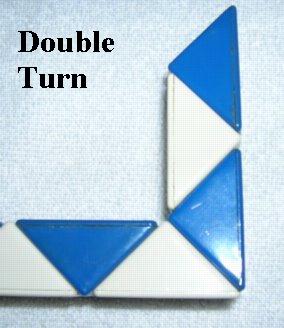

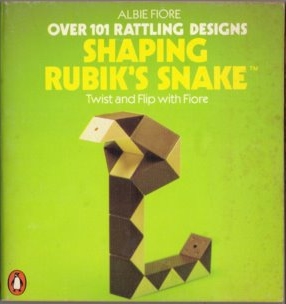

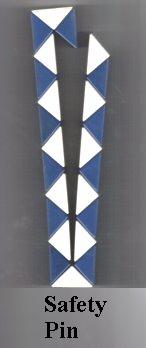

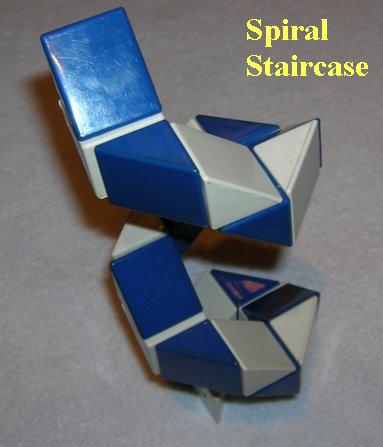

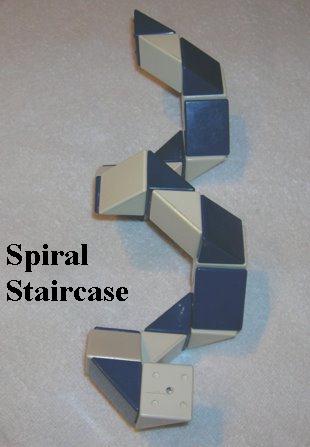

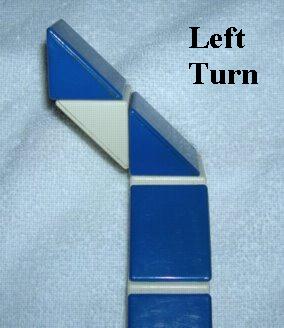

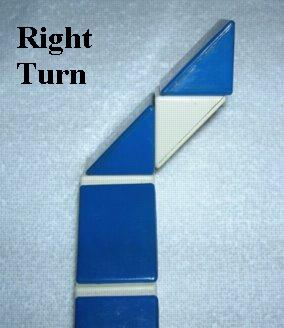

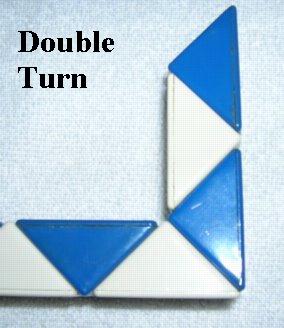

New Shapes for Rubik's Snake

Where to Buy Puzzles

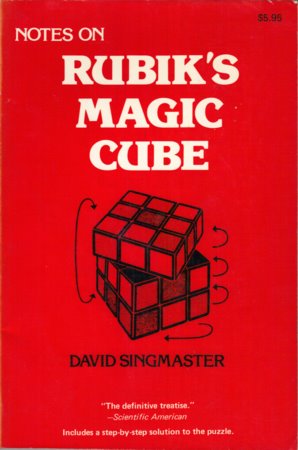

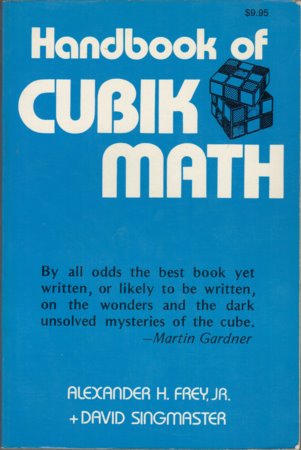

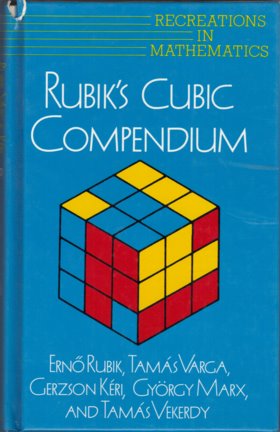

Annotated Bibliography

Encyclopedias

A Survey of Rubik's Cube Maneuver Catalogs

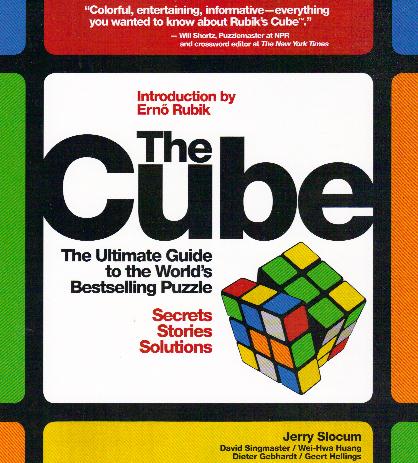

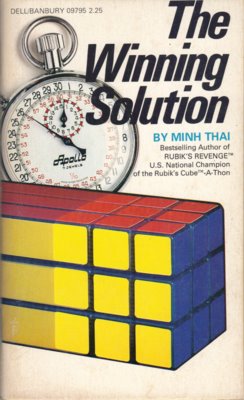

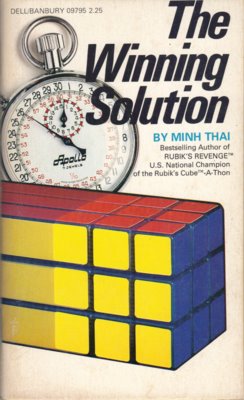

Mastering the Cube Literature: A Short Guide to Books on the Magic Cube

of Ernő Rubik

Sequels to the Cube: Books on Big and Little Cubes, Snakes,

Pyramids, and Chains

Who's Who in Cubology

Appendices

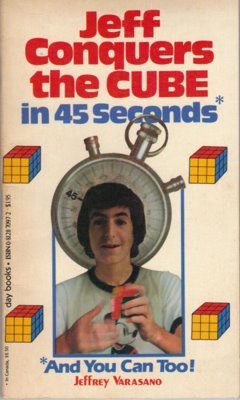

Appendix 1 -- Varasano method for

speedsolving 2x2x2

Appendix 2 -- MES and xyz notation

Some of the material in this booklet appeared in

WGR

(numbers 1-12) between 1982 and 1994. Portions of the bibliography

appeared in Inscape #1 in December 1982, and are reprinted here

in edited form with the kind permission of Donald G. Keller. All of the

photographs and scans herein are from my personal puzzle collection; in

some cases you can see the wear and tear on books and puzzles which are

over 35 years old.

Most of the puzzles discussed herein are protected (or may have been in

the past) by patent, trademark, or both. Rubik and Rubik's

Cube (among others) are

registered trademarks of Seven Towns,

Ltd.

V-Cube is a trademark of Verdes

Innovations S.A.

A Microhistory of Twisting Puzzles

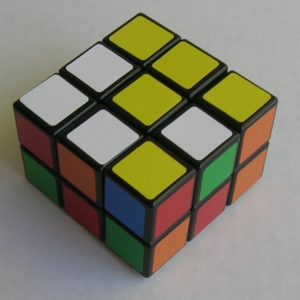

In 1974, Ernő Rubik, a Hungarian professor of

interior architecture, conceived of a new puzzle design, a 3x3x3 cube

with six solid-colored sides, where each of the six outer layers could

turn independently. He named it Bűvös

Kocka (magic cube), and was able

to construct a prototype and solve the puzzle of unscrambling a

mixed-up cube. Within a few years it was being manufactured and sold in

Hungary, and in 1979 Ideal Toys paid 1 million dollars for exclusive

worldwide rights to manufacture it, at which point the puzzle was

renamed Rubik's

Cube. This was the first published item of a genre now known

as twisting puzzles. Although the original patent has

expired, Rubik's Cube is currently a trademark of Seven Towns, Ltd., based in

London, England.

Before the end of 1981, Rubik's Cube

was followed up by a number of puzzles, each of which might be

considered to be a sequel to it in some sense. Rubik himself

created

the Magic Snake, made out of 24 triangular prisms joined by springs,

which allow the snake to be twisted into a large variety of shapes.

Ideal Toy Corporation devised a puzzle called The Missing Link, an

interesting modification of the Fifteen Puzzle popularized by Sam Loyd.

Tomy

manufactured a tetrahedral puzzle called Pyraminx, which was actually

conceived by Uwe Mèffert prior to the cube. In 1982,

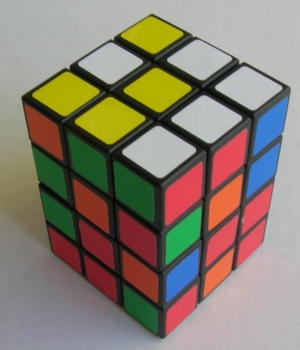

Ideal brought out a smaller

version of the Magic Cube called Rubik's Pocket Cube (a 2x2x2 cube)

and a larger version called Rubik's Revenge (4x4x4). A number

of

books appeared in order to help the enthusiast with this new

torrent of puzzles. The Cube was a worldwide craze for

a few years, spawning

dozens of related and unrelated puzzle designs, several bestselling

books, at least three newsletters, and huge media publicity.

It

won numerous awards, including the 1980 Spiel des Jahres for Game of

the

Year. A World Championship for speed solvers was held in June of 1982,

but

not much more than a year later, the bubble had burst and the

craze was over, and it

would be 11 years before a second World Championship was held.

More than a decade after the original Cube

boom

ended, another fertile

period of puzzle development began, fueled by a number of companies

which entered the puzzle field or expanded their operations, several

magazines (most notably Cubism For Fun) providing

coverage of puzzles,

and mail order catalogs offering a greater selection of new and old

puzzles.

A Quick Account of my Cubing History

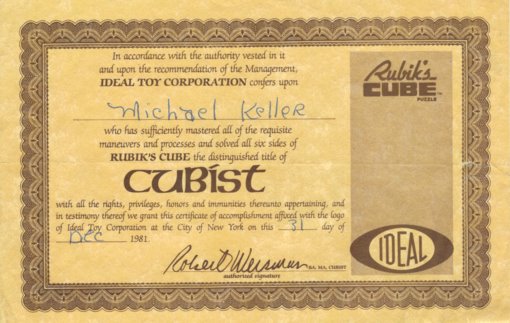

I bought my first Cube in 1981. I was not able to make any

headway

with it until I read Douglas Hofstadter's first article in Scientific

American. I managed to solve it a couple of times, but

it took a long

time and required handwritten notes so I could undo long

conjugations.

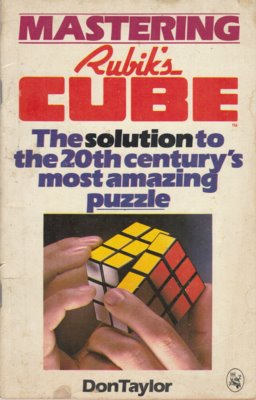

I then learned a complete and reasonably short solution from Don

Taylor's Mastering Rubik's Cube. I was able to

get my solution time under 2 minutes (with my brother Richard as

witness) late

in 1981 and got a

certificate from Ideal Toys (scan above). The

solution I

gradually developed,

which is presented here, roughly follows Taylor's general

outline (with a major addition from solutions by Cyril Östrop and M. Razid Black), and

with some phases combined and many shortcuts added. I

published the first issue

of WGR in November 1982, including a solution to Pyraminx which was the

first twisting solution I worked out without consulting other sources.

My solutions to Skewb, Orb, and ImpossiBall appeared in the next few

issues. I also wrote a short guide to books on the cube which

appeared in my brother Donald's science fiction fanzine Inscape (most of this is reprinted in the bibliography, with much new material).

The Cube fad collapsed during 1983, and a number

of solutions I had written up by hand never appeared in WGR. A

sequel I wrote to the Inscape article also never appeared; most

of the

material from

both articles appears here in modified form.

I had probably not solved a cube in five years or so when I saw

descriptions of the Mirror Cube on the Internet in late 2008. I ordered

one from an eBay dealer in Japan, and while I was waiting, I started

relearning the details of my Cube solution, which I had mostly

forgotten. The arrival of the Mirror Cube rekindled my interest in

twisting puzzles in general, and I started work on this booklet in

mid-2009.

For

speedcubers who'd like to laugh at me, my personal records at the

moment are: 2x2x2 11.50s (but a fluke 9.94s), 3x3x3 47.77s, Icon

1:52.10, 4x4x4

2:20.24, 5x5x5 4:22.61, 6x6x6 8:43.53,

7x7x7 14:01.40, 8x8x8 23:09.22, 9x9x9 40:19.63, combined solves [2x2x2

through 7x7x7] 34:15.37,

[2x2x2 through 8x8x8] 1:00.15.35, one-handed 2x2x2 50.03, Twist 3x3x3 2:06.98, one-handed

3x3x3 2:31.50, Mirror 2:43.81, Fisher Cube 2:46.14, Mixup 3:17.60, cube pattern replication 3:48.72, Tactile

6:04.41,

Shepherd's Cube 11:29.53; Pyraminx

15.41s, Skewb 18.34s (fluke 16.83), Redi

Cube 35.43, Master

Pyraminx 1:48.65, Kilominx 1:48.87, Orb

1:58.62, ImpossiBall 5:00.91, Master Pyramorphix 5.01:53, face-turning Octahedron

7:06.59, Megaminx 6:12.06, Gigaminx 52:19.16, Professor Pyraminx 11:56.53. Fewest

moves (including slice and

multiple turns): Redi Cube 23 turns, 3x3x3 40 turns, Petal Pyraminx, 72 turns, Twist

3x3x3 76 turns,

4x4x4 128 turns, 5x5x5 252 turns, Megaminx 265 turns.

Most of these were timed by hand

with a stopwatch or online timer, and all of them were

solved with no

preexamination time.

A Brief Glossary of Terms Used in Twisting Puzzles

The following terms will be used throughout the various puzzle

solutions:

antislice move -- a turn of two opposite layers in opposite directions.

baryon -- a sequence of moves which twists three corners in place 120

degrees in the same direction

center -- a piece located in the interior of a turning layer, usually

with one colored

facet. The

3x3x3 cube has six centers, which are fixed to the central spindle of

the puzzle, and can rotate but not move to other faces. In cubes

with pictures or other patterns on the faces, the orientation of the

centers matters. Larger cubes have more than one center piece per

face; they can freely move to different faces via slice

moves. In shapeshifting 3x3x3 puzzles, a center is the

middle of a turning

layer, and can change orientation but not position. It

has four orientations, and may have one, two, or four colored

facets. Some puzzles, like ImpossiBall,

Pyraminx, Square One, Dino Cube, and Redi Cube, have no centers.

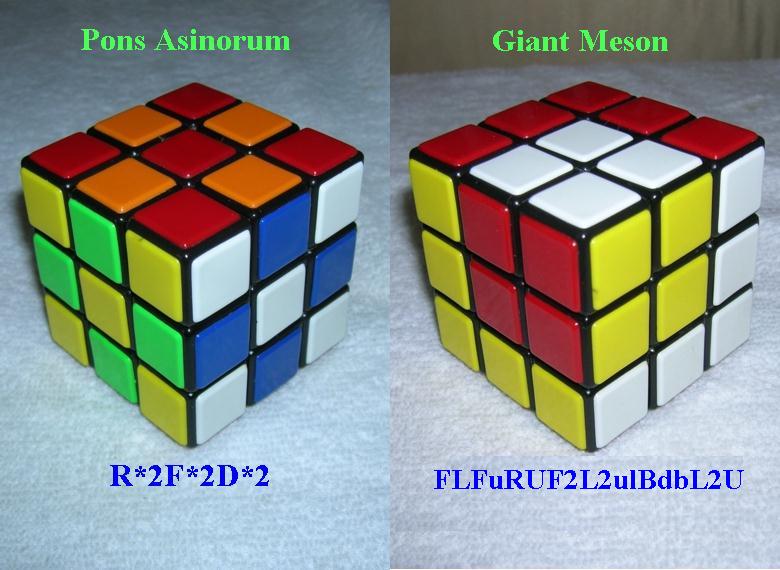

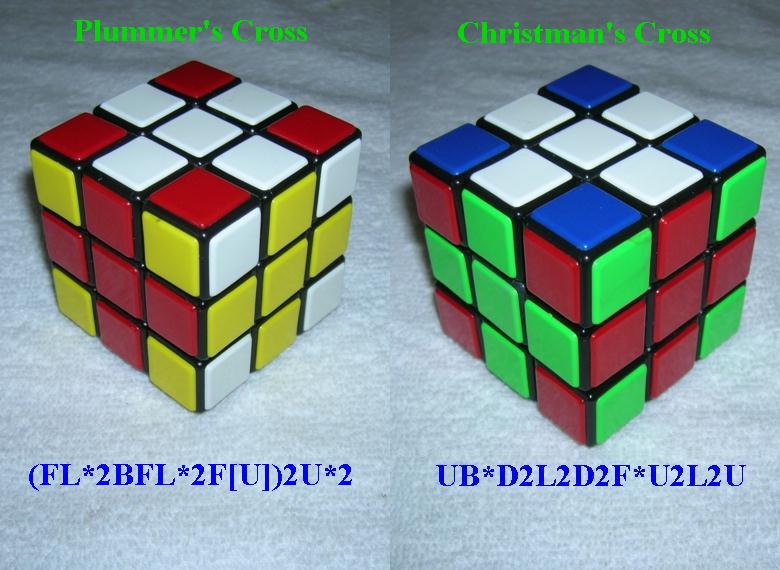

Christman Cross -- a pretty pattern for the Cube in which a cross

appears on

all six faces, with the colors grouped in

threes.

commutator -- a sequence of moves of the form ABab, where two moves (or

sequences)

are performed, then the inverse of both are performed. Longer

commutators are possible; e.g. ABCbac or ABCacb (see, for example, the

Pyraminx solution).

conjugation -- a modification of a sequence by

adding one or more setup turns to place pieces in certain locations.

After performing the main

sequence, the setup turns are performed in reverse order and reverse

direction. This is described in more detail later.

corner -- a piece which is part of three

mutually perpendicular turning layers, and which can be

twisted in 120 degree

increments, so that it has three possible orientations.

On a normal cube it has three colored facets, and cubes (of

any size from 2x2x2 up) each have eight corners. In

shapeshifting puzzles, a corner may have one, two, or

three colored facets, and on some puzzles (e.g. Master Pyramorphix),

the orientations may be visually

indistinguishable.

deep move -- a turn of an outer layer and one or more adjacent parallel

layers at the same time

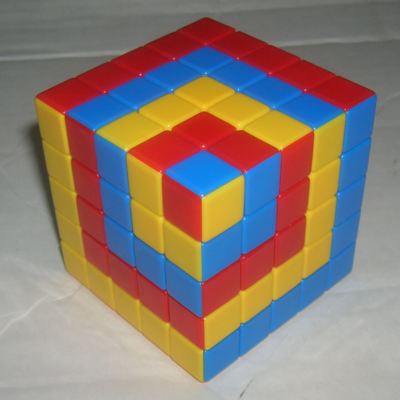

Dots -- a Cube pretty pattern in which each side shows a center of one

color

surrounded by eight facets of a second color (e.g. R*F*L*B*).

Also

useful as the

basis for routines which rotate centers on picture cubes and

swap centers on larger cubes (4x4x4 and above). Cubes larger

than 4x4x4 allow for a bullseye pattern with a single facet or 2x2

square surrounded by two or

more circles.

double bicycle -- a sequence of moves which swaps the locations of two

pairs of pieces

double edge flip -- a sequence of moves which reverses the orientation

of two edges at once

double meson -- a sequence of moves which twists four pieces, two in

each direction

edge -- a piece which is part of two

perpendicular turning layers, and usually has two orientations.

On most puzzles it has two colored facets which meet along a

line segment. The 3x3x3 Cube has 12 edges, Pyraminx has 6, Square

One 8,

Skewb

and

Pocket Cube zero. On order-3 puzzles edges can be

reversed in place

(flipped). Larger

cubes have multiples of 12 edges: 24 for

4x4x4, 36 for 5x5x5, 48 for 6x6x6, etc. On puzzles with four

layers, edges cannot be flipped in place; their orientation is

determined by their position (e.g. Master Pyraminx; see the diagram in

that section). On the

Mixup Cube, edges can be twisted 90 degrees via half-slice moves.

In shapeshifting 3x3x3 puzzles, edges may have up to three colored

facets, but still only two orientations. In some puzzles (e.g.

Fisher

Cube and octagonal barrel variant cube), some or all edges have only

one color and both orientations look the

same. In others (Master Pyramorphix), edges have one color but

are asymmetric, so flipped Edges stick out from the normal puzzle

shape.

equator (Alexander's Star, ImpossiBall) -- the band of pieces lying

between two opposite faces

face -- a flat visible surface formed by a group of pieces (usually)

sharing the same color. There are

six faces on a Cube of any size, four on Pyraminx, etc.

Occasionally the face is not flat (as in ImpossiBall). In normal cubes,

the face is part of a layer and turns as a unit (but see Skewb and

Square-1 as exceptions).

facet -- an individual segment (of one color) of a center, edge, or

corner piece. A center usually has one facet, an edge two,

and a corner three. Each facet will have a sticker or tile of (or

be painted) a particular color.

flip -- to reverse the orientation (and colors) of an edge while

leaving it in the

same location (a 180 degree rotation). In most puzzles, every sequence

of moves flips an even

number of edges (perhaps zero).

inverse -- a sequence which performs the exact opposite of another

sequence. It is derived from the original sequence by reversing the

order and direction of the turns. For example, the inverse of ruR2

brB2 ubU2 is U2BU B2RB R2UR.

layer -- a group of pieces which turn as a unit (9 in the 3x3x3 Cube)

meson -- a sequence of moves which twists two corners in place 120

degrees in opposite directions

middle -- centrally placed (used as an adjective while center is used

as a noun). In particular, the middle layer of the 3x3x3 cube is

the layer in between the first and last layers to be solved (typically

the Up and Down layers), and middle edges are the four edges in that

layer. On 5x5x5 (and larger odd) cubes, a middle edge

is the centermost of a set of three edge pieces.

orient -- to turn a correctly positioned piece so that its colors match

those of correctly positioned adjacent pieces

parity -- a mathematical principle which limits the possible

configurations

which can occur in a puzzle. For example, the number of edges

which are flipped in a scrambled 3x3x3 Cube is always an even number.

piece -- an outer unit of a puzzle. It usually

has one, two, or three facets, each a different color. The 3x3x3 cube has 26 pieces.

place -- to put a piece in the correct location and orientation at the

same time; usually done one piece at a time

Plummer Cross -- a pretty pattern for the Cube in which a cross appears

on all six

faces, with the colors grouped in pairs

position -- to put a piece in the correct location without regard to

orientation; usually done three or four pieces at a time

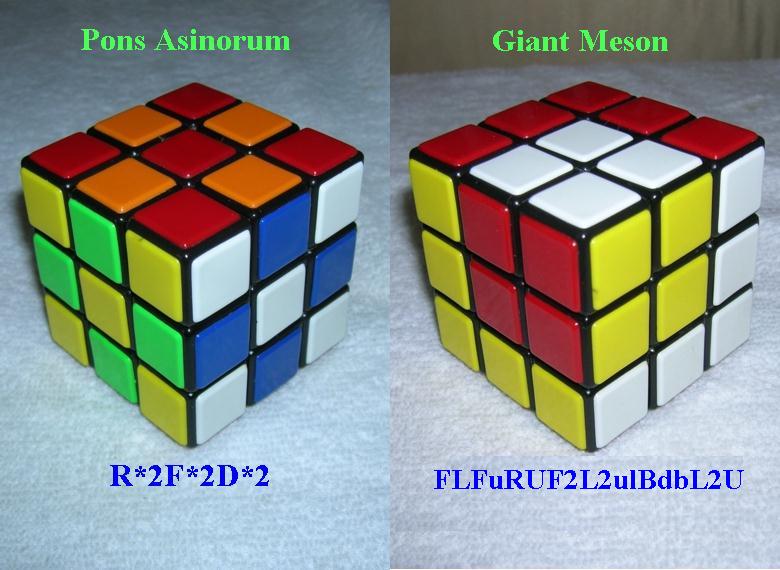

Pons Asinorum -- the simplest Cube pretty pattern, formed by half turns

of all six outer layers (L2R2F2B2U2D2 or R*2F*2D*2),

producing a checkerboard

on each face. Also possible on 5x5x5 and larger odd-ordered

cubes, turning every alternate inner layer (or on even-ordered cubes

with the center being 2x2).

pretty pattern -- a sequence of moves which place a previously

unscrambled cube or other twisting puzzle into an attractive

arrangement, usually symmetric

quark -- a one-third (120 degree) twist of a corner

shapeshifter -- a puzzle which often changes shape from turn to turn (e.g.

the Square One and Pyramorphix families; Mirror, Fisher, Twist, Axis,

and

Mixup cubes)

slice -- the subcubes lying between two opposite layers (e.g. 4 edges and 4

centers in each

slice in the 3x3x3 Cube)

speedcubing -- competition solving against the clock, which generally

requires very

complex algorithms, fast reflexes, and a well-lubricated cube

Start -- the unmixed goal position of a twisting puzzle; normally each

face of the puzzle is one color. Always capitalized when used as

a noun in this sense.

Sune -- a very fast sequence which twists three corners while

moving three edges in a tricycle. It can act as a tricycle

tip -- a three-colored piece on tetrahedral puzzles (the Pyraminx

family) connected only to one larger corner. It is

trivially fixed by aligning its colors with the attached corner.

tricycle -- a sequence which cyclically exchanges the locations of

three pieces

twist -- to change the orientation of a corner without changing its

location

twisterflipper -- a sequence which performs flips and twists

simultaneously. Coined by M. Razid Black and Herbert Taylor in their

book

Unscrambling The Cube.

wing -- a two-colored piece on larger Pyraminxes where the two

facets meet only at a point.

wring -- a simultaneous 90 degree turn of an outside and middle layer

together, and an additional 90 degree turn of the outside layer

alone, done in one motion.

Solving the 3x3x3 Cube -- an Intermediate Solution

What Is Wrong With Most Beginner's Solutions?

Almost every layer-by-layer beginner's solution (whether on the

Internet

or in printed books) has at least one fundamental flaw: they recommend

placing all four Up corners before doing the middle edges.

This

requires using long sequences of 7-9 moves (including a setup move

where needed), instead of simple 3-4 move drop or push insertions, to

place the middle edges. This makes the solution longer,

especially when flipped or misplaced edges must be pushed out

of the middle layer and then placed correctly. It is much

easier for

a beginner to place three Up corners, then all four middle edges, then

place the last Up corner using a tricycle or the Upside-down Insertion we will show later. Then you can learn the shortcuts of swapping middle

edges, then placing Up corners at the same time you place or flip a

middle edge.

Beginner's solutions to the Cube often use

pictograms instead of notation to show each move in a sequence

(somewhat like trying to teach someone music without teaching them the

basics of music notation). They are usually slow and inefficient,

frequently requiring a sequence to be applied twice (or more!) rather

than give an inverse version. They rarely use slice moves, and

generally require 100

moves (turns) or more to complete a solution. [A recent trend is an appalling waste of time

called the daisy,

putting all four Up edges in the Down layer without regard to position,

then placing them in the correct Up position by turning the Down layer

to the correct position and making a half turn.]

What is an intermediate solution anyway?

Speedcubing solutions to the Cube normally require the solver to

memorize

more

than 100 different sequences to handle dozens of individual positions

in particular situations, and the individual sequences are often long

and hard to remember (using turns of only a few faces, and few

repetitive patterns). They frequently use a mixture of three different

notations for regular, slice, and whole cube turns, and often

require a

reorientation in the middle of a long sequence. Speedcubing

methods need 57 different sequences just to handle every possible orientation of the last layer; we

will see later how this can be done a little

less

efficiently with three

variants of a single sequence.

The solution we present here is somewhere in

between a beginner's solution and a speedcubing solution. It

doesn't require you to learn 100 or more move sequences in order to

solve the

cube, but allows solving the cube in well under two

minutes, usually taking no more than 80 moves, sometimes considerably

less. I am currently under 1 minute about 40 percent of the time

(recent average 65 seconds) using

this method with an ordinary (not speed) cube, and occasionally have

been under 60 moves. The best time I have recorded since I started

working on this booklet is 47.77 seconds. The move sequences I

use are the ones which I feel are

the easiest to memorize, as they are either relatively short or have a

strong pattern to them.

I count, as some analysts do, both 180 degree turns and slice turns as

single

turns. Others insist on counting by outer layer quarter turns, so

that a 180 degree outer layer turn or a 90 degree slice turn

counts as two turns, and a 180 degree slice turn counts as four.

Even by this more restrictive counting system, I can usually get a

solution in under 100 quarter turns. [There's another system which

counts outer layer turns, but both 90 and 180 degrees count as one; any

slice

turn counts as two.]

Notation

We use the standard Singmaster (English language) notation for the

Cube, where the six faces/layers are designated Front, Back, Left,

Right, Up, and Down, and clockwise 90-degree turns of each layer are

designated by capital letters. We designate anticlockwise turns using

lower-case letters (rather than using a prime or minus sign); I think

this makes the notation easier to read. 180-degree

turns are designated by the capital letter followed by

a 2 (these may be made in the clockwise or anticlockwise direction,

whichever you find more convenient; R2 and r2 have the same effect).

We also designate slice turns

(of one of the three middle layers) with an asterisk indicating a

90-degree clockwise turn of the adjacent middle layer in the same

direction: R* means to move the slice in-between R and L in the same

direction as an R turn. (This is much easier to remember for

non-mathematicians than the MES notation used

elsewhere). The same turn

in the opposite direction is L* (so R*2 and L*2 have the same effect).

Individual

pieces are designated, where necessary, by a single letter for centers,

two letters for edges (UF is the edge shared by the Up and Front

faces), and three letters for corners (BLD is the corner shared by the

Back, Left, and Down faces).

In the rare cases where we show a specific

reorientation of the whole cube in the middle of a sequence, we

designate a turn of the entire cube in brackets, again avoiding the

unnecessarily complex

notation used elsewhere, with whole-cube turns designated with xyz

notation. [F] means to turn the

whole cube in the direction of a Front turn, so that the Front face

stays the same and the Left face becomes the new Up face (this has the

same effect as FF*b). We will often add spaces to notation to

make it easier to

read and to clarify the structure of the sequence. The six main

clockwise turns, and an example of a slice and an anticlockwise turn,

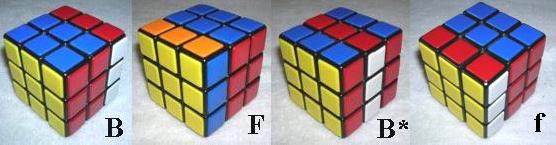

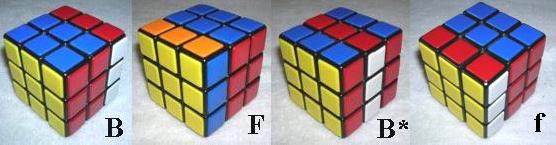

are shown above in a variety of diagrams and photos.

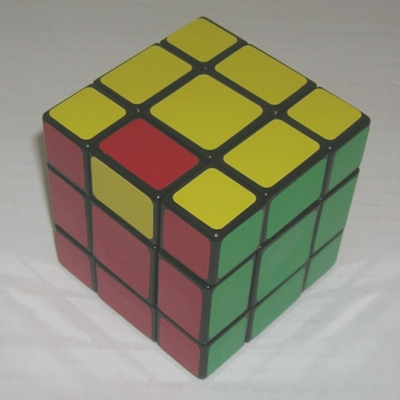

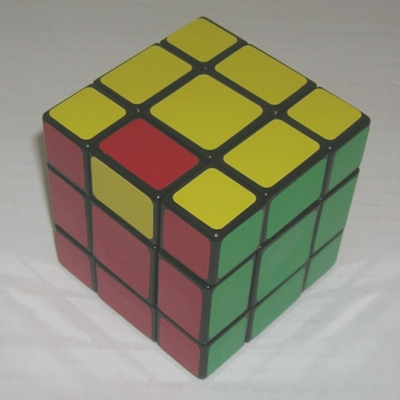

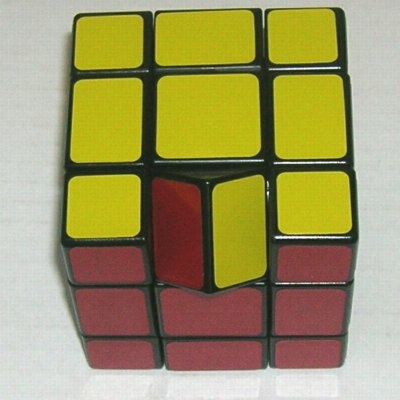

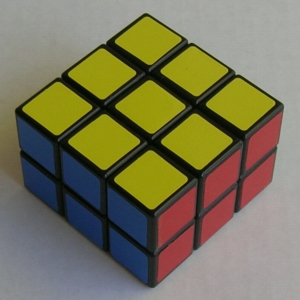

Diagrams

show the color pattern which Ideal quickly made standard on its

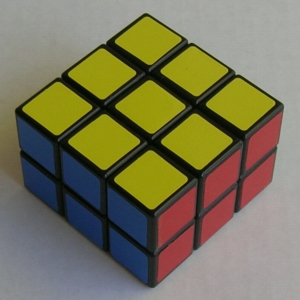

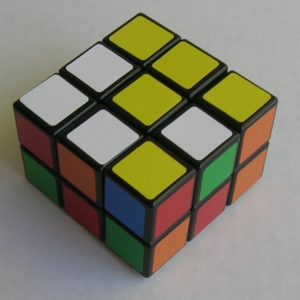

cubes (shown in the four small photos above right):

blue is

opposite white, red is opposite orange, and green is opposite yellow.

Why do we want to use slice turns?

Some cubists do not like using slice turns, because they are

slower for speed cubists to perform, and because they complicate the

notation. But slice moves are used in speedcubing, sometimes in

disguise, and they are essential for solving larger cubes (4x4x4 and

up). They also make it much easier to understand and remember many

sequences. For example, a routine to flip all 12 edges can be notated

very concisely as ((R*U)4[UL])3.

An 8-move sequence like

(R*U)4

which flips four edges in place (diagram above) was apparently first

discovered by

Bernard S. Greenberg and named the Spratt

wrench,

in a posting to the Cube Lovers mailing list on

August 10, 1980. (He also noted that a simple, though not efficient,

double edge

flip is (R*U)4(UR*)4.)

Solving methods which do

all of the

corners first (like Thai's and Varasano's: see the Bibliography) make

heavy use of slice

moves.

Some sequences also use an antislice turn,

which

consists of turning two opposite faces simultaneously in opposite

directions (though both clockwise from their point of view). Antislice

moves can sometimes produce short and clever

sequences, such as Thistlethwaite's routine (RLUrlU2)2

to turn a

center

on a picture cube

180 degrees. or the elegant double edge swap

LRU2lr[U]lrU2LR.

A deep move is a turn

of two layers (an outer layer and the adjacent slice) at the same time,

for example RR* or rL*. We will use this in our 3x3x3 solution in

several instances, particularly where a conjugating move

overlaps the beginning of a

standard sequence. (Speedcubers sometimes have a special

notation for deep moves, and often express slice turns as a deep move

followed by a reverse of the outer layer). Deep moves are

used frequently in solving the 4x4x4 and larger cubes.

A faster equivalent of the antislice move is a move is sometimes

called a wring;

it consists of turning a middle slice and outer layer together

and continuing the outer layer turn another 90 degrees,

e.g. R*R2, which has the same effect as RL[R]. This would

actually be performed as either the deep move R*R followed by another

R, or R followed by a deep move R*R, but all in one motion.

An anticlockwise

wring looks like L*r2 (equivalent to rl[L]). A very

clever (though not especially useful)

routine which flips all 8 of the Up and Down edges is (F*F2

R*R2)3 (equivalent to six antislice moves: (RLUDFB)2).

A slight modification of this (done twice, replacing the initial wring

with a deep move) gives a quadruple edge flip (though not the most

efficient one), flipping all four of the

Up edges: (U*U (R*R2 U*U2)2 R*R2)2 U2.

A more useful sequence using wrings is R*R2 B2 L*r2 F*b2 R2 B*B2, which

swaps two opposite pairs of edges on the Up layer (see the Fifth Stage of our 3x3x3 solution).

How do we find good move sequences?

Useful sequences can be found using a number of

techniques. One basic kind of move which is widely used in

solving the first layer of a puzzle is an insertion:

putting a

piece into a target location which is in between two other pieces

already in place. There are two main techniques for

insertions, which we can call drop insertions and push insertions.

For simplicity, we will talk about the 3x3x3 Cube, though the

same principles apply to other twisting puzzles. Consider the

situation in which we are

trying to insert an corner from the Down layer into the Up layer.

In a drop insertion, we turn a side layer to move the target

location from the Up layer into the Down layer, turn the Down

layer to rotate the desired piece into the target location,

and turn the same side layer in the opposite direction we

turned it initially. In a push insertion,

we turn the piece directly into the target position, turn it

away at an angle, then reverse the first two turns. The push

insertion is an example of a commutator,

a sequence of turns of the form XYxy (you may see such a sequence

referred to as a sexy move or sledgehammer).

In solving the Pyraminx and other

puzzles,

we make use of slightly more complex commutators of the form XYZyzx.

Repeating commutators often allows us to build powerful routines with a

high amount of repetition, which makes them easy to remember

(note

these especially in the solutions we'll see later for Skewb and

ImpossiBall). Commutators are useful enough that some easy

puzzles can be solved with nothing else.

Another way of generating sequences is by combining two sequences in a

way that some of the moves at the end of the first sequence are

reversed at the beginning of the second. For example, I found the

Upside-Down Insertion (F2D)2F2D2F2

(described later) by combining two

well-known sequences: the

I-Swap F2DF2dF2,

and the sequence (F2D2)3,

which swaps FL with FR and LD with RD. Joining these, we get

F2DF2dF2F2D2F2D2F2D2.

The middle section dF2F2D2 cancels out and

becomes D, and we drop the last D2 because we don't care about the Down

layer yet. The second half unswaps FL and FR which were swapped

by the first half, and the result is a pure insertion from the Down

layer which has no effect on the middle layer. This

sequence is also useful in solving the 3x3x2 and 3x3x4 cuboid puzzles

we

will see later.

Rubik himself discovered the double edge flip (R*U)2R*U2(L*U)2L*U2. He may

have discovered the Spratt Wrench too, and realized that he could join

it to an almost-mirror image of itself, (UL*)4. If you just join those

you get (R*U)4(UL*)4,

which flips UL and UR once and three middle-slice edges (UB DB DF)

twice, resulting in a pure double-edge flip of 15 moves. But what

happens when you stick U2 in the middle? Now the original UL is

going to be flipped a second time (and UR not at all), and instead of

flipping the original UB a second time, we 're swapping the original UF

instead. Now it becomes R*UR*UR*UR*U(U2)UL*UL*UL*UL*,

and the underlined section mostly vanishes: the four consecutive U's

become nothing, R* and L* cancel out, and what's left is just U2.

Adding another U2 at the end to undo the middle one, we have Rubik's

discovery.

Another kind of sequence alternates turns of two faces, turning one

face the same direction each time (sometimes with double turns) and the

other in alternating directions. The best known of these is

the Sune, RUrURU2rU2, named by

Lars Petrus as part of his 3x3x3 solution. It twists three

corners in the same direction and cycles three edges (on the 2x2x2 it

acts as a pure baryon). Other similar sequences are useful

in solving the Megaminx, Redi Cube, and other puzzles.

Another way of finding sequences is by adapting sequences from one

puzzle to another. The 3x3x3 corner tricycle lURuLUru which can be used on any

size cube, can be adapted to dodecahedral puzzles like Kilominx and

Megaminx.

Outline of the 3x3x3 solution

The solution we describe here has six stages:

(1) Place the four edges in the Up layer -- these are done one at a

time, but with each edge we place, we try to eliminate any problems

with

edges yet to be placed.

(2) Swap any middle edges which are already in the middle layer into

their correct locations, regardless of orientation.

(3) Place the four Up corners while placing and fixing the remaining middle

edges. We use a group of short sequences (3-8 turns) with dual

purposes, with each sequence trying to place/fix an Up corner and a middle

edge at the same time whenever possible.

(4) Flip the cube over so that the unsolved layer is now Up. Place the

corners

in the correct positions, regardless of orientation.

(5) Place the edges in the correct positions, regardless of orientation.

(6) Orient all of the edges and corners simultaneously, using one or

two applications of Benson's

Twisterflipper.

First Stage -- Placing the Upper layer edges

The first stage in solving the Cube is to place

the four Up edges in their correct positions around the Up center.

To do this efficiently, we want to get as many of the

edges into good positions (either in the Down layer with the Up colored

facet facing down, or anywhere in the middle layer), so that we can put

them into the correct Up position with a single turn of a side layer.

The bad positions, in contrast, are in either the Up layer

or Down layer with the Up color facet on one of the side faces.

An edge in the Up layer with the Up facet facing up is good (shown as

beige, above center) if there is only one, or if by chance there are

more than one in the correct positions. A properly mixed cube

shouldn't have any edges matching the center color when you begin

solving, but if you do have

such an edge, you can consider it already correctly placed as the first

edge.

Otherwise the first edge can be placed anywhere in the Up layer; the

remaining edges

must be placed in the correct positions relative to the first edge

placed, regardless of the positions of the centers (we will

save a lot of unnecessary Up turns this way). When moving an edge from

the

middle layer into the Up layer (with a turn of a side face), we

should always try to save moves by converting

bad edges into good edges at the same time. There are two ways of

doing this: pushing out a bad edge from the target position, or putting

a bad Down edge into the middle layer (by putting it under the target

position by turning the Down layer). Sometimes you can do both at the

same time. Since we can place the first edge anywhere, we

should always choose, if possible, to put it somewhere that pushes out

a bad edge (and convert a bad Down edge if possible too).

If there are

any edges in the middle layer which need to go to the Up

layer, we should begin with one of these, but make sure turning it

into the Up layer will not make another middle layer edge into a

bad edge by pushing it into the Down layer). Consider

the example above right: it is tempting to just turn

Front anticlockwise, putting the white-yellow edge into the Up

layer and pushing out the bad green-white edge. But doing this

will make the red-white edge bad by pushing it into the Down layer

flipped the wrong way. Instead we want to place the red-white

edge first by turning Left anticlockwise, putting it

in the Up layer with the white facet Up. But before

we do that, we turn Up clockwise to put the bad green-white edge

into the target location, and also turn Down clockwise so that the

bad orange-white edge is underneath the target location. Now when

we turn Left anticlockwise, we have placed the first edge and converted

both of the bad edges into good ones in only three turns. [It

will actually only take four more turns (fbDR2) to

place the

rest of the edges.]

The diagram above shows the first edge

(white-orange) already

placed, although the orange side facet is not aligned with the orange

center (we will not align the Up layer with the middle edge centers

until the first two layers are completely finished). The

small white and yellow squares show the target location for the

white-yellow edge. We want to get the white-yellow edge into

one

of the three positions shown, so that a turn of F or f or F2 will put

it in the correct spot. If the white facet of the

white-yellow

edge is in a good location, we can turn either the Down layer or the

Down and middle layers together (a deep move) to put it in one of the

three locations shown. If the white-yellow edge is

in the Up

layer with its white facet on a side face, or with its white facet

Up but in the wrong position relative to the first (white-orange) edge,

we can first turn the side layer it is in (F, L, or B) so that

it

goes into the middle layer. If it is in a bad position in

the

Down layer, we can again turn the side layer it is in to put it in the

middle layer. but we must not displace an Up edge already placed, so if

it is underneath one of the edges already placed, we must turn the Down

layer to put it in a different side layer first, before turning that

side layer.

Below are some more examples of placing two bad edges at the same

time. In the first two examples, U* is not a slice move,

but part of the deep move dU*, in which the bottom two layers are

turned together anticlockwise.

Let's

now look at a complete example of placing all four edges when all of

them are bad at the beginning. In the position above left, we have

two white edges in the Up layer but flipped, and two in the Down layer

with their colored facets Down. We begin by turning l

anticlockwise, to pull the bad edge out of UL and bring the bad edge at

DL into the middle layer. Next we turn b anticlockwise, putting

the

white-yellow edge into an Up slot and pushing the bad

white-green edge out of that slot. The white-red edge belongs at

UR, so we turn U clockwise to put the target at UF, then turn F

clockwise to put the white-red edge into its correct location and bring

the last bad edge from FD into the middle layer. Now ul

(both anticlockwise) puts the white-orange target at UL and turns the

white-orange edge into it, and ur (both anticlockwise) puts the

white-green target at UR and puts the last edge there.

We don't need to turn U again to match the Up edges with their

side-center colors yet, because the Up and middle layers will operate

independently in the next stage.

Some utility routines for fixing troublesome edges

If you haven't pushed out all of the bad edges by the time you have

placed the first two or three edges, you may find the last edge or two

in a troublesome position. The routines shown above should help: the

first two show how to fix the last edge when it is in the correct

location but flipped, or in the Down layer in a bad

position. The third routine lets you move an edge in the

wrong place (from UF to UR), and the fourth lets you switch two

adjacent edges.

When two bad edges on the Down layer are adjacent and they need to be

moved into adjacent up positions, they can be placed simultaneously

with one of the two routines above. The first moves each edge to

the position directly above it, but flipping it in the process.

The second swaps their positions and flips them at the same time.

Second and Third Stage Shortcuts in Solving the Cube

Rubik's Cubic Compendium presents a rather

hard-to-learn method

of simultaneously solving the upper corners and middle edges

of the Cube (devised by a group of cubists at Cambridge University).

Speedcubers have developed even more elaborate methods, particularly

the second phase of the CFOP system (this requires 42

sequences

as described in Speedsolving the Cube by Dan

Harris). But it is

possible to achieve reasonably good efficiency without memorizing a

huge set of sequences. The following method allows the solver to solve

the upper corners and middle edges quickly. It was devised by putting

several ideas from books by other cubists together with a few ideas of

my own.

Second Stage -- Preplacing Middle Edges

Stage 2 requires the solver to find all middle edges

which are already in the middle layer, even if in the wrong position or

orientation. These will be edges without the color of the

Down face (in our example, blue). The simple sequences

shown below allow any edges already in the middle layer to be swapped

into their correct locations

(relative to the four side centers).

At this point their orientation is not important -- we are going

to flip edges during stage 3. The bottom diagrams show an X-ray view of

the

middle layer looking down through the Up layer.

The 4th sequence, the I-Swap, also moves a corner from DRF to URF.

This should be used as often as possible; it can be used to get a

headstart on Stage 3 by inserting a corner whose white face is in

the Down layer from the Down layer to its Up position, or pushing

out an Up corner which is in the wrong place (occasionally both at

once). An alternate version of the I-Swap, which moves a corner from

DLF to URF, is faster, but dislodges ULF (actually putting DRF

there). If you want to swap two middle edges without disrupting any Up

corners,

(F2D2)2F2 also swaps FL and FR.

Most of the time you will only find one or two edges which

belong in the middle layer and are already there. A

single

edge can almost always be moved to its correct location with a V- or

I-Swap: turn the whole cube so any correct edges are at LB, or

LB

and RB (the only tricky case is a single or double swap when LB and RF

are correct: this requires a V-Swap

followed by an I-Swap; see the two examples below, where correct edges

are shown as solid black). Two edges can usually both be

swapped

to their correct locations with one of the four routines above (except

in the second case shown below). More complex swaps of three or

four edges need a V or X swap to put two of the edges in their correct

spots, followed by an I-swap to fix the remaining edge or edges.

Third Stage -- Placing Up Corners and Placing and

Flipping the

Remaining Middle Edges

An important point to understand is that although we are going to be

trying to place (or fix) Up corners and middle edges

simultaneously with each sequence we carry out in Stage 3, the

Up layer and middle layer are

independent of each other,

until we finish the stage, when we will align them. Each

sequence in this stage can potentially operate on both an Up corner and

a middle edge (except for the last two sequences which insert the

fourth Up corner without disrupting any of the middle edges).

Since Stage 2 often puts middle edges in the correct position but

flipped, we

first look at move sequences which insert a corner from the Down layer

into the Up layer, while flipping a middle edge already in the correct

location. In the examples pictured below, we want to flip the

orange-green middle edge, while inserting the white-yellow-red corner

into its correct Up position. We first turn the whole cube so

that the flipped edge is at RF, turn the Up layer so that the

white-yellow-red target location is at URF, and turn the Down layer so

that the white-yellow-red corner is in the correct location for the

selected sequence. If the corner has its Up facet (white in our

examples) on the Down face, it should begin at DRF. If its Up

facet is on any side face, it should begin diagonally opposite, at

DLB. Now perform the indicated routine, depending on the

position of the white facet. The Column Flip is actually two

Drop Insertions joined together. The other two routines, which

are mirror images of each other, each bring a corner from the

diagonally opposite location, by reorienting the corner in the Down

layer and putting it in position for a Drop Insertion.

The Column Flip should be used whenever possible; i.e. anytime there

is both a flipped middle edge and a corner in the Down layer with its

Up facet on the Down face. If there are no such corners, but

more than one flipped middle edge, use one of the other two routines if

possible.

If you have an Up corner in the correct position, but twisted,

there is another set of routines to twist an Up corner in place

(clockwise or anticlockwise), while optionally putting a new middle

edge in place. Turn the bottom two layers together so that RF is

either the target for a middle edge, or at least an incorrect location

(remember that we don't want to put the last middle edge in place

unless we are placing or fixing the third Up corner at least). Then

(if you are placing a middle edge) turn the Down layer so that the edge

being placed is in the correct spot (there is one valid location for

any edge, depending on which way it is flipped and in which direction

we need to twist the corner). The first and third twists are

well-known routines, and we will use them again when solving Rubik's

Pocket Cube. The second and fourth routines are the same as the third

and first routines, except that the Down turns are 180 degrees.

Now we use the four routines below

to move any of the corners which belong in the Up

layer, but are currently in the Down layer with their

Up-colored facet on one of the side faces, into their correct

positions,

including orientation. If the edge at RF is correct (or flipped), turn

the whole cube so

that the edge at RF is not a correct one (flipped or not). If

an edge in either of the two corresponding Down layer positions

also belongs in the middle layer, we will also place the new

middle edge at the

same time, though here orientation doesn't matter (Cyril

Östrop's book was

the inspiration for this technique), and we want to turn the whole cube

so that

RF is the target of the edge in the Down layer we want to move. Turn

the Up layer if

necessary so the target for the corner we want to move is at URF, and

turn the Down layer so that the corner we want to move is at DRF,

and do a push or drop insertion as appropriate.

We will continue using these routines to put in Up corners (and

middle edges at the same time if possible), jumping back to use the

Edge-flipping insertions as needed, trying to get at least three Up

corners correct. It is best to avoid putting the fourth

middle edge in place until you have

three Up corners correct.

If there are no corners in the Down layer which belong in the Up layer,

then some of the Up

corners must be swapped with each other. Force one of them out using a

Drop Insertion. You can put a middle edge in too at the same time if

there are not already three in place; in any event make sure that RF is

not correct, so that you don't displace an edge already in its correct

spot. Then put the corner you've just sent to the Down layer

into its correct Up location, which should push out another bad Up

corner.

Once you have three Up corners in place, you should finish

putting each remaining middle edge in place (possibly there is

only one at this point), using whichever insertion will put it

in the correct orientation: turn the whole cube so that the target is

at RF,

turn the Up face if needed so the unplaced Up corner is at URF, and

turn the Down layer so the edge you want to place is in the correct

location, then perform the correct Insertion.

You can actually do Drop Insertions from other positions; e.g. if the

green-orange edge is at FL with its green facet on the left face, you

can insert it via

rD2R. In fact, although we will not show all eight possible positions,

when you are placing edges alone, any middle edge still in the Down

layer will either already be in position for a Push Insertion, or can

be inserted from where it is via a variant Drop Insertion (turn

whichever of the Front or Right faces is the color of the edge facet

not on the Down face, then turn the Down layer so that the edge moves

into the side layer you just turned, and undo the side layer turn.

So the Drop insertions may also be rDR, rD2R, Fdf, or FD2f.

Occasionally the last Up corner and the last middle edge can be put in

correctly at

the same time using one of the four Corner/Edge Insertions, but usually

either they are not aligned properly or the edge is flipped the wrong

way. In this event, it is quicker to put the middle edge in by

itself, but flipped, unless you still have another middle edge flipped.

If all of the other three middle edges are correct, and you want

to put the last edge in backwards, follow the same procedure as

the previous paragraph, but consider the orientation of the edge

reversed. Finally put the last corner in using the Edge-flipping

Insertions

we learned at the beginning of the phase, which should both flip the

last

middle

edge and place the last Up corner.

If you make a mistake and accidentally insert the last corner in the

wrong

orientation while a middle edge is flipped, you can fix both using a

routine we are going to learn soon, Benson's Twisterflipper.

Turn the whole cube so that the almost complete Up layer becomes the

Left layer, and the flipped middle edge is at UF (also turn the new

Left layer if needed so that the twisted corner is at ULF).

Now do ruR2 brB2 ubU2 if ULF needs to be twisted

clockwise, or U2BU B2RB R2UR

if it needs to be twisted anticlockwise.

If you prefer, you can insert the last middle edge correctly, and

use one of the first two routines shown above to put in the last Up

corner

without disrupting the middle layer. These routines also may be used

when you make a mistake, or otherwise end up

in a situation where all edges are correctly placed and oriented

while an upper corner still needs to be placed (you may do this

intentionally, if the sequence which inserts the third Up corner also

inserts the last middle edge correctly). The third routine, which

flips a middle edge without affecting the Up layer, can also be used to

fix a mistake, or when all of the edges are in place (two of them

flipped) with only one Up corner left to insert. In the latter

case, put the last corner in using an edge-flipping insertion, and then

use the Middle Edge Monoflip on the last middle edge. The

Upside-Down Insertion will also be useful in solving the

3x3x4 Cuboid puzzle we

will see later.

Turn the Down face so that the last corner comes to DFR, while its

target location is UFR.

If the last corner is upside-down, we can insert it with a special

sequence (above left) which combines two well-known sequences (removing

an unnecessary move): the I-Swap we learned at the beginning of the

second stage, and

the simple double-edge swap (F2D2)3.

If the last corner has its correct upper face on one of the

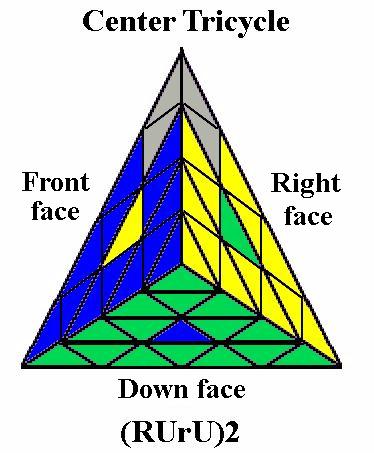

side faces, the Corner Tricycle can be used to place it correctly. If

the upper face color is on the right side of DFR, turn the whole cube

so that the target is Right and the corner to be inserted is at ULB

(green in the diagram above middle). If the upper face color is on the

front side of DFR, do d (backwards Down turn) and

hold the the whole cube so

that the target is the Front face and the corner to be inserted is at

UBR (red in the

diagram above middle). Then perform the standard Corner Tricycle lURuLUru,

which we will meet again right away when we begin placing the corners

in the last layer.

Fourth Stage -- Placing the Up layer corners

Most speedcubing methods require dozens of sequences to be learned in

order to solve the last layer (the CFOP system has 57 sequences to

orient the last layer and 21 more to permute the last layer). This is

extremely fast and efficient, but at a huge cost in memorization.

Our system requires only 11 sequences (three of which are inverses and

two minor variants) instead of 78, once you understand conjugation and

learn

how to use Benson's Twisterflipper effectively.

Stage 4 is an easy one and requires performing only one sequence of

seven or

eight turns. Pick one of the Up corners (one with its blue facet

on the Up face if there is one) and turn

the Up layer so that that corner goes to its correct location,

then turn the whole cube ([U], [u], or [U2]) so the correct corner is

at URF. Now either two, three, or four corners are correct

(disregarding

orientation). If four are correct, you can

proceed to Stage 5.

If three are correct, the corners need to be cycled clockwise (the

corner

at ULF needs to go to ULB), or anticlockwise (ULF needs to go to URB).

Use the Corner Tricycle below far left, or its anticlockwise

inverse, below second left), to put the remaining corners in the

correct position. The

Corner Tricycle is one of the best-known and easiest routines to

learn, alternating left/right turns with up turns in alternating

directions (we just saw this in Stage 3 as a method of inserting the

last Up corner without disrupting middle edges). Proceed to Stage

5. [A version of this without twists, used in

speedcubing, is bRbL2BrbL2B2. Another variation, which twists two corners instead of three, is LFlBLflb.]

If two adjacent corners are correct, turn the whole cube so that

the

correct layers are at ULF and ULB (i.e, if URF and URB are correct,

turn [U2]; if URF and ULF are correct, turn [U]), and do the

Adjacent Corner Swap (third below), which is identical to the Corner

Tricycle except that the last turn is a half turn. Proceed to Stage

5. If two diagonally opposite corners (i.e. URF and ULB) are

correct, do

the

Diagonal Corner Swap (below right) and proceed to Stage 5.

Fifth Stage -- Placing the Up layer edges

There are five possible cases after the corners are in the correct

positions.

In one case out of 12, the four edges are all in their correct

positions (though perhaps either two or all four are flipped).

Two-thirds of the time, one edge is

correct and the other three need to be cycled, either clockwise or

anticlockwise. In this case, turn the whole cube (as in Stage 4,

keeping the Up face in place and rotating

around the vertical axis) so that the good edge is at UR. Now use the

Edge Tricycle

or its inverse (below left) to fix the other three edges. The

anticlockwise tricycle is

identical except that the two single U turns are anticlockwise. Speedcubers

prefer a longer but faster edge tricycle which

uses only Up and Right turns: R2URU(ru)2rUr,

which cycles UL=>UR=>UF.

Only the Tricycle is strictly necessary, since double swaps

can be done by doing a tricycle twice, but it will speed up solving to

use the two double swaps, which are easy to learn because of their

strong repetitive patterns. The Edge

Cross-Swap (an elegant palindrome), which occurs in one case out of 12,

is considered fast

enough to be used in speedcubing methods (e.g. Speedsolving

the Cube,

p. 65, case #17). [Another clever routine which does an edge cross-swap

with wring moves is R*R2 B2 L*r2 F*b2 R2 B*B2 (equivalent to R*R2 B2L*r2 [U] L*r2 F2R*R2).] The Edge Angle-Swap occurs

in one case out of 6.

Sixth Stage -- Orienting the Up Layer pieces

Warning: the method described here for the last stage will

seem fairly complicated

at first, and if you have not solved the cube before, you may want to

learn a simpler but less efficient method first. If so, skip

ahead.

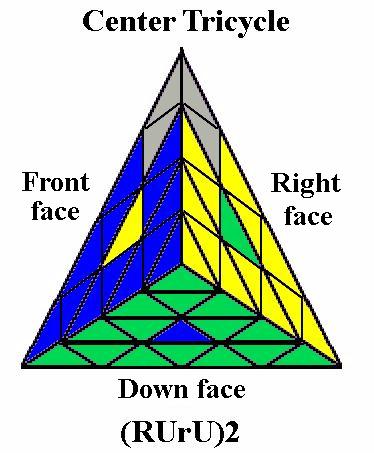

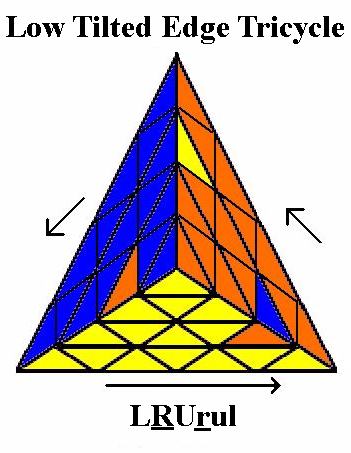

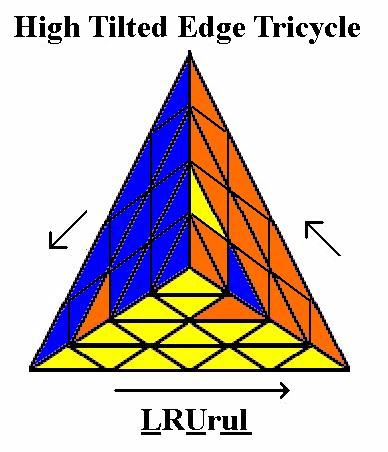

One of the most powerful maneuvers in the world of cubology is a 9-move

twisterflipper discovered by David Benson, ruR2 brB2 ubU2.

This sequence twists the three up corners ULF, URF, and URB clockwise,

and flips the two up edges UF and UR. A flat view

of the cube immediately before performing the maneuver is shown below

left, with its inverse (U2BU B2RB R2UR) below middle

and a conjugated

variant below right. Note that the variant begins with a deep

move, turning two layers in the same direction instead of one, so that

it is actually only ten moves long. You can actually disregard

the variant if you wish, and just treat it as one of the Conjugated

Twisterflippers we'll see in the next set of diagrams, but it's worth

learning for reasons we'll see later.

You can also perform the sequence as a set of the same three turns

performed three times, with a 120 degree rotation around a

diagonal axis in between: (ruR2[BU])3

and its inverse (U2BU[LD])3.

Below each color picture is a skeleton diagram of the top face showing

which corners

need to be twisted (+ = clockwise, - = anticlockwise) and which edges

need to be flipped (+). This maneuver, the shortest known

twisterflipper, is flexible enough

to provide the basis for a complete method of orienting the up layer.

All of the 35 twisterflippers can be produced using one or two

repetitions of this move and/or its inverse or variant. Usually the

first repetition will be the standard version, which we will

designate @, but in a few cases we will need the inverse or variant.

The basic idea is to put ourselves, regardless of what configuration of

twists and flips we began in, into a configuration with three

corners twisted (they will all be twisted in the same

direction) and two edges flipped. We'll call this a three-two

position.

Unless we are already in such a configuration, the method we are using

here will

require two

repetitions. Before we look in detail on how to handle the

two-repetition cases, let's look at the three-two positions; there are

only twelve of these, six with the three corners needing to

be twisted clockwise, and six with the three corners needing to be

twisted anticlockwise. The only difference in these two sets of

six is whether we use the regular or inverse Benson sequence (and

the regular allows us to combine two turns in two cases).

There are six positions of the two flipped edges relative to the three

twisted corners, one of which is the standard shape above left and

above middle. The other five positions are shown below. These will

require conjugation: one or two setup

moves to put the edges and corners into the correct shape, then undoing

the setup moves in reverse order after performing the Benson

sequence. The first two positions require two turns

before performing the Benson sequence, though in the first sequence (if

the twists are clockwise) the second setup turn (underlined) combines

with the first move of Benson to form an R2 turn (I usually do it

anticlockwise

anyway, so the sequence becomes br2 uR2 brB2 ubU2 RB,

12 moves in total. The third and fourth positions need just

one setup move. (The fourth position is a rotated form of the

variant we have already seen above right, and it can be done with a

deep move as shown if the twists are clockwise, but for simplicity

we show it with a simple one-move setup, so that we can do it the same

way if the twists are anticlockwise). The last is the worst

case, and needs two slice setup moves (the second, underlined again,

becoming part of a deep move if the twists are clockwise; i.e., it is

the variant

Benson in between F* and B* slice moves). Remember that if the

three corners need to be twisted anticlockwise, we are going to do the

inverse Benson sequence, above middle, instead of the

standard @ sequence, and we lose the first of the underlined

one-move shortcuts. The fifth case below actually becomes F*

L* U2BU

B2RB R2URR* B*,

with the next-to-last turn becoming a deep move, again for a total of

12 moves.

Now what do we do if there are four, two, or zero corners

twisted, or zero or four edges flipped? We want

to hold the cube (rotating the whole cube around the vertical axis

while keeping the Up layer up) so that the first Benson Twisterflipper

flips

half of the edges which need to be flipped (one out of two, or two out

of four), and twists one corner correctly and two incorrectly, putting

us into a three-two position. It would be possible to show a diagram of

every single case, but it's better to understand the concept rather

than memorizing 57

individual cases.

If all four corners, or none, are twisted (which happens a little

over 1/4 of the time), any of the four positions will

work as far as the corners are concerned. If all four edges, or

none, are flipped, or two opposite edges are flipped (which happens

half the time), again, any position will work as far as the edges are

concerned. If

we're in one of the easy positions, we can then perform the regular or

inverse Benson, choosing whichever one fixes one of the three

corners which we are twisting: if two of them need to be twisted

anticlockwise and one clockwise, we use the normal Benson, if two

clockwise and one anticlockwise, we use the inverse (see example 1

below). If

none of the corners are twisted, we can use either one. In any event,

we

end up in one of the three-two positions already described above.

[There are three cases where it is preferable to use the variant Benson

instead of the normal Benson, to avoid the worst conjugation cases --

see examples 1, 2, and 6

below.]

So the only positions we have to think harder about are three corners

twisted in the same

direction, two corners twisted in opposite directions, and two adjacent

edges flipped. If all four corners, or none, are twisted, and two

adjacent edges need to be flipped, we hold the

cube so that the edges to be flipped are either at UF and UL, or UB and

UR, and

do the normal or inverse Benson as described in the previous paragraph

(see example 3 below).

If three corners are twisted, we're going to hold them in the normal

position so that the untwisted corner is at ULB. If two edges are

flipped, we're already in one of the three-two positions we've already

learned above. If no edges or all four edges are flipped, we're

going to do something odd: we're going to do a Benson Twisterflipper in

what seems to be the wrong direction (the normal Benson if the corners

need to be twisted anticlockwise, or the inverse if they need to be

twisted clockwise). This will reverse

the twist of the corners and flip two of the four flipped edges (or

flip two unflipped edges). In any case, we end up with two edges

flipped and three corners still twisted, a situation we already

know how to handle. See examples 5 and 6: note that we

prefer the variant Benson in several cases, as described above.

If two corners are twisted in opposite directions, we need to hold the

corner which needs to be

twisted anticlockwise at ULB, so the first Benson will twist the

other one and the two untwisted corners all clockwise, leaving us with

three corners which need to be twisted anticlockwise. Again, this

might seem like we're messing the cube up more, but remember that we

want to get to a position with three corners twisted in the same

direction. As long as the edges are not in one of two troublesome

positions, we do the standard Benson, once again ending up in a

three/two position we

know how to finish. See examples 7 and 8 above.

The only two edge positions which cause a problem are the two positions

where

two opposite corners are twisted in opposite directions, and two edges,

which are adjacent

to one of those corners, are flipped. Any way we hold the cube will

either flip both

edges or twist both corners, neither of which we want to do. The

solution is to hold

the cube in the same way we have just described, with the corner

needing to twist anticlockwise at ULB. The two edges to be

flipped are either at UB and UL, or at UF and UR. Now

we use the variant Benson (that's the second and more important reason

we want to

learn it), L*ruR2 brB2 ubU2 R*, beginning with a deep

move and finishing with a

slice move. This will flip the edges at UB and UR,

twist the corner at UFR clockwise (fixing it), and twist the two

untwisted corners at UFL and UBR so that they both need to be twisted

anticlockwise, once again reaching a three-two position.

The orientation phase should take no more than 23 moves, even in the

worst cases, and the cube will be solved.

[It is possible, by the way, to reverse the order of stages 5 and

6, doing all of the orientations first and then fixing the edge

positions. I usually do stage 6 first if the pieces which need to be

oriented are already in the standard V-shaped Benson configuration.]

Additional orientation sequences for the last layer (four

elegant routines)

If you want a little more efficiency at the cost of learning some extra

sequences, you can learn some more sequences which do corner rotations

alone or edge flips alone at the end. The most useful of these are two

which

were discovered by Ernő Rubik himself. These can actually be used

as an alternative to the Benson method, though you will still need to

understand how to conjugate the two Rubik routines.

Rubik's Meson (above left) twists the front-right corner clockwise and

the back-left

corner anticlockwise on the Up layer. Note that the first six turns

are simply repeated to complete the sequence, and that the six moves

consist of three moves and a sort of mirror image of those moves. This

is a pretty easy sequence to learn, despite being 12 moves long, since

it is a six-move sequence repeated twice. If the

corner which needs to be twisted anticlockwise is the front-left

corner, do an L before (to put it at the back-left position)

and an l

afterwards; if it's the back-right corner, do a B before and a b

after.

If you need to twist three corners in the same direction, you can

do Rubik's Meson on two of them, leaving you with another (conjugated)

Meson, or you can learn Thistlethwaite's Baryon, shown below left.

This is one of the longest and hardest sequences we present in this

book, and

if you learn it, you also need to learn the anticlockwise (inverse)

version as well (BRbr

U2 (lB2Lb)2 U2).

Rubik's Flip flips the front and back edges on the Up layer.

Note again the pattern: the first three slice moves are in

one direction, and the last three are in the opposite direction.

The Up turns are all in the same direction, with the third and last

being 180 degree turns. If the two edges to be flipped are

adjacent, hold them at the front and left, do lb to put the

left one

at the back, so the same routine as above, and do BL to

finish.

Rubik's Flip will be essential to know if you eventually

learn to solve the 5x5x5

and

larger cubes, since it never disrupts center pieces and can be modified

to flip similar portions of two edges. [Speedcubers

on 3x3x3 may prefer a slightly longer but faster version:

(R*U)3R*U2(R*U)3R*, but this disrupts centers and isn't useful on

larger cubes.]

If

you need to flip all four edges, you can do Rubik's Flip twice, or use

the Quadruple Edge Flip shown below, center. The Quadruple Edge

Flip also has a strong pattern, but note that the first and second half

end with quarter turns rather than half turns. The

Quadruple Edge Flip unfortunately does disrupt centers somewhat if you

use it on larger cubes to flip partial edges; we will later show a

routine based on the

Spratt Wrench which can flip

four partial edges without disrupting centers.

Monoflips and

Monotwists -- a simpler but slower method for Stage 6

An alternate sequence for double edge flips is: FD* F2D*2 Fuf

D*2F2

U*fU,

which flips FU and FL. The advantage of this sequence is that it can be

used to flip FU and FB as well, by changing the quarter Up

turns in the middle and at the end to half turns: FD* F2D*2

FU2f D*2F2 U*fU2. This is a modification, using

slice moves, of a sequence described in Donald Taylor's book Mastering

Rubik's Cube (pp. 28-29). It is an example of a technique

called a monoflip (also sometimes called isoflip),

a

sequence of moves which flips one edge in a layer (in this

case the Up layer). The flipped edge is then replaced by another edge

by turning the Up layer, and the sequence of moves is then reversed,

which flips the second edge and returns the rest of the cube to its

original state.

A corresponding technique for corner twists is a monotwist.

The

monotwist (RfrF)2

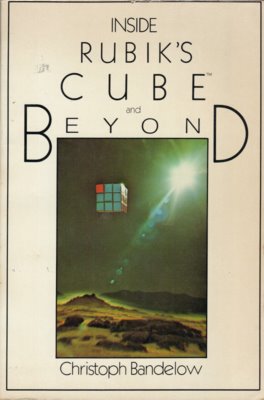

and its inverse, described in Christoph Bandelow's book Inside

Rubik's

Cube and Beyond, can be built into a complete set of

routines for Up

corner twists. Start with any corner which needs to be twisted at URF.

Each corner in turn is twisted clockwise using (RfrF)2

or

anticlockwise using (fRFr)2.

After twisting a corner, turn the Up layer (not the whole cube) to put

the next bad corner in position, and continue using the correct

twist.

Any combination of twists (meson, baryon, or double meson) in any order

can be fixed. Each monotwist disrupts the two lower layers, but

the combined effect of opposite pairs or three of the same kind leaves

the rest of the cube in the same position it began in.

A shorter (but a bit slower) monotwist pair, rDRFDf

for clockwise twists and FdfrdR

for anticlockwise twists, must be used in opposite pairs to keep the

lower two layers correct. This has the disadvantage, in the

case of a baryon, of requiring that one of the

three corners must be twisted the wrong way twice.

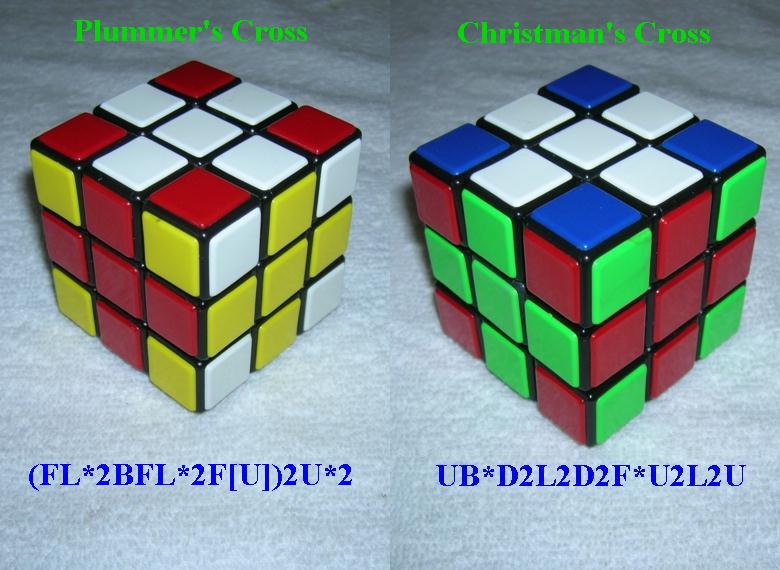

Pretty Patterns

There are hundreds of these; we will show only a

few of the most elegant ones. The crosses were first

discovered by David C. Plummer and David Christman

respectively.

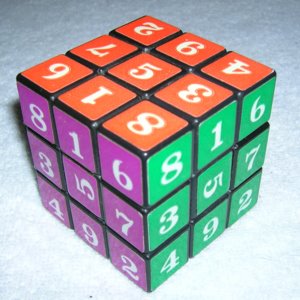

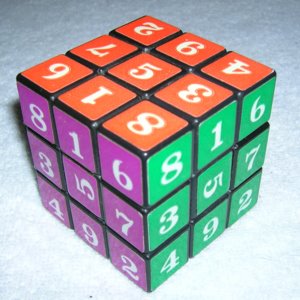

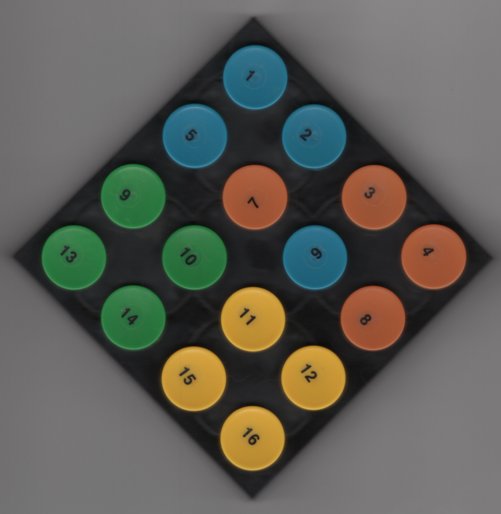

Picture Cube

Almost since its inception, many versions of the Cube have been made

with pictures on the

stickers. Solving such a cube is essentially identical to the standard

cube except

that you may have centers which are rotated at the end. The photograph

above shows a cube with numbers in the form of a 3x3x3 magic square

(nowadays you can also find Sudoku Cubes). The orange 5 needs

to be rotated 180 degrees and the purple and green 90 degrees clockwise

and anticlockwise respectively. We will notate this as {U2Fr},

indicating that the Up center needs a double turn, the Front center a

clockwise turn, and the Right center an anticlockwise turn. So we need

routines to rotate centers independently. Christoph Bandelow's book Inside

Rubik's Cube and Beyond has a detailed set of routines

performing center turns, but two routines are sufficient to get all of

the centers turned correctly. The sequence R*B*L* F R*F*L* f,

using a modification of the Dots pretty pattern, turns {fR}. This will

allow

you to finish all of the centers except perhaps one. The neat routine

(RLUrlU2)2, discovered by Morwen B. Thistlethwaite,

turns {U2} (the

equivalent version using wrings is (R*R2BL*r2U2)2. A

third

routine, a variant of the first, might speed up the process: R*B*L*

F2

R*F*L* F2 does {F2R2}. A double Spratt Wrench, (R*U)8, does

{U2B2F2D2}. Some speedcubers prefer the longer but faster ((rURU)5) to

turn {U2}.

Cubes with full pictures on each face add another layer of complexity,

as it is necessary to figure out which pieces go on which layers, like

solving six separate jigsaw puzzles.

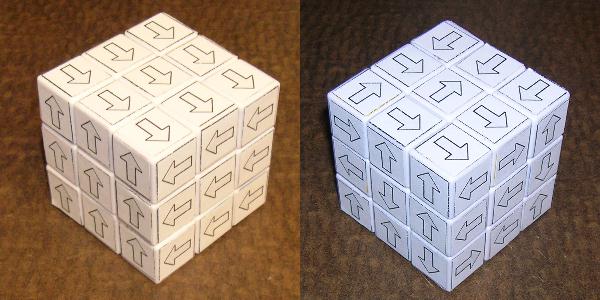

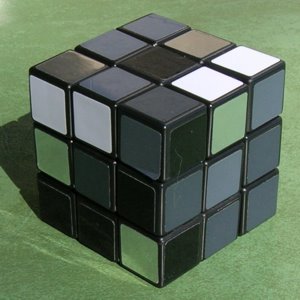

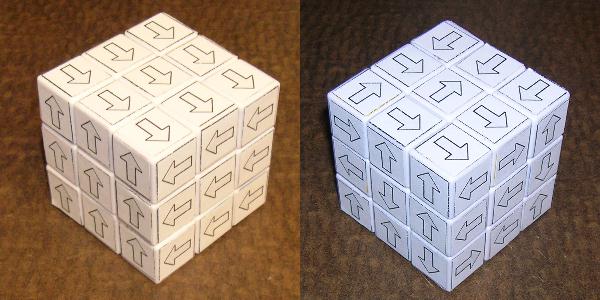

Other Coloring Patterns

Rubik's Icon (above left) is a new edition of the

Cube, published by Winning Moves.

It has a normal coloring pattern, but an unusual selection of colors:

black, white, mirrored (silver), and three different shades of gray,

and is hard to photograph well. It's brutal to solve

quickly; my best is 1:52.10, and I'm usually around two and a half

minutes. Shepherd's Cube

is a pattern devised by

Alistair

Shepherd, with black and white arrows pointing in six different

directions. The photo above center shows my handmade model in

the Start position; arrows on opposite faces point in opposite

directions (Left arrows point toward the Back face (I messed this up

when I first put on the stickers), Back arrows point toward Down; Down

arrows toward Left). The photo above right shows the scrambled

Shepherd's

Cube.

I have managed to solve this several times, but I'm just starting to

get the hang of what I'm doing -- it's the worst puzzle I've ever seen

for trying to

visualize what's going on. You can even end up in an apparently

impossible position where everything is solved except for one center

turned 90 degrees. My first timed solve was 11:29.53.

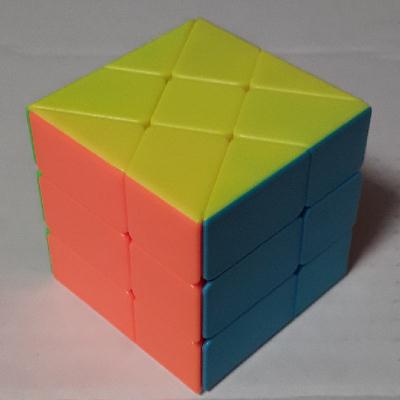

Shape Modifications

A good number of variant puzzles have been designed by altering the

shape of the outer pieces, often by making cuts through the cube at

angles different from 90 degrees.

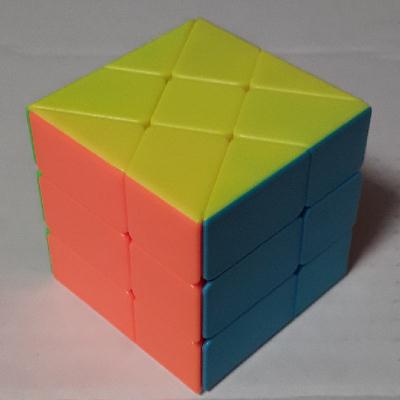

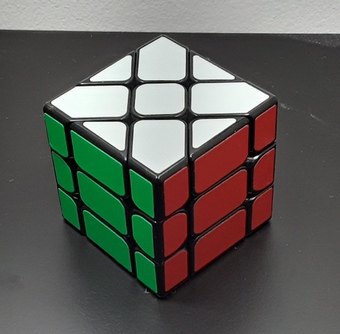

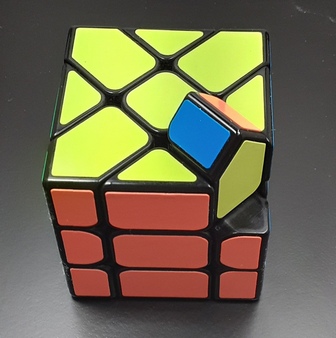

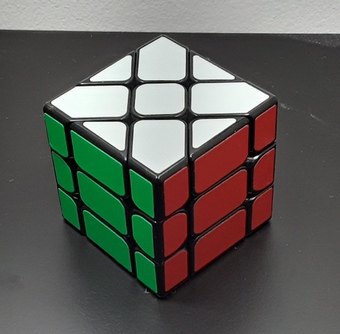

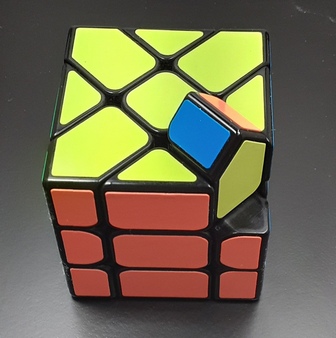

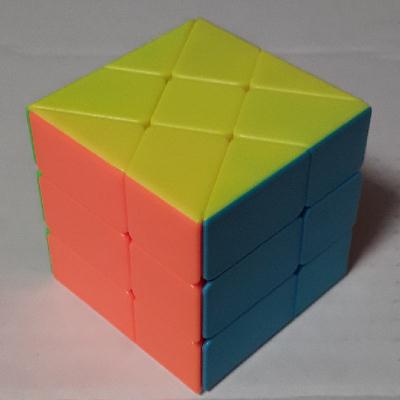

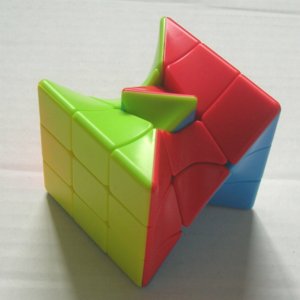

Fisher Cube

The first true shapeshifting puzzle

was invented by Tony Fisher in the 1980's. By

cutting through the

cube at 45 degree angles in two directions, he created a puzzle in

which edges, corners, and centers interchange their

functions (solved cube above left). When scrambled, it

produces a very erratic shape (above center). The Fisher

Cube has 12 pieces which appear to be

edges, but eight of them (those in the Up and Down layers) act as the

eight corners of a normal cube. The other four (in the

middle layer) act as centers for the four layers which turn at 45

degree angles. The Up and Down layers turn normally; their

centers are true centers. The eight house-shaped three-colored

pieces act as eight of the 12 edges; the one-colored pieces on the side

faces (which look like centers) act as the other four

edges. Keeping in mind that edges and corners on the Up and

Down layers swap roles, the Fisher Cube can be solved by basically the

same method as the normal 3x3x3, with the addition of the Picture

sequences above which turn centers. The first two layers

can be solved as usual; if any middle layer centers are twisted, leave

them for the end, since some last-layer sequences disrupt middle layer

centers. For example, Rubik's Flip, (R*U)2R*U2(L*U)2L*U2,

twists the the Front and Back centers 180 degrees, while the standard

quadruple edge flip twists the Back center 90 degrees clockwise. It is possible to end up with one center twisted 90 degrees,

which looks

like an impossible position, but it can be fixed by simultaneously

turning either a yellow or white center 90 degrees in the opposite

direction using the same sequence R*B*L* F R*F*L* f described

above. You can also have a single edge flipped; this can be fixed

with a conjugated Rubik's Flip (third diagram above).

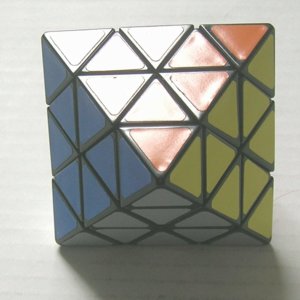

Windmill Cube

A different cutting pattern, at 30/60 degrees, produces

only six pieces on each of the vertical faces. The corners and Up

and Down edges have only two facets, while middle edges have only one

facet. This is solved in the same way as the Fisher Cube.

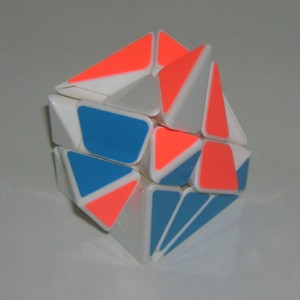

Mirror Cube

Originally known as the Bump Cube, it was invented by Hidetoshi

Takeji,

and submitted to the Puzzle Design Competition for the 2006

International Puzzle Party (shockingly, it did not win a prize, being

beaten out by the much less interesting Floppy Cube among others).

The Mirror Cube is essentially a 3x3x3 Cube, but each of the six outer

layers is a

different thickness. When the faces are turned, the cube turns into a

jumble of differently sized rectangular prisms. Three of the photos

above show

the gold version I bought recently (there are also

pointless six-colored versions, designed by someone who didn't

understand the concept of the puzzle). The Mirror

Cube can be solved by most of the usual methods, but it is hard to see

quickly where each piece goes (push insertions work better than drop

insertions). There should be a lot of scope for

making interesting pretty patterns with the Mirror Cube (the third

photo shows a Giant Meson, on the original silver model I bought in

2008). It

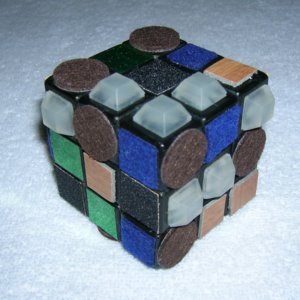

is possible to solve the Mirror by touch, as with the Tactile cube

shown

below,